In this article, we will give an overview concerning why there is a need for textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible. We will also define some important terms, introduce our readers to the major text families of the Hebrew Scriptures, and illustrate ways to access them online and in print. The following article (Textual Criticism 102) will summarize some general procedures in textual criticism and demonstrate methods that are helpful in identifying (and correcting) problems in the biblical manuscripts. The end goal is to have a clearer understanding of what is contained within the Holy Scriptures, so that we may better follow the God of Israel who inspired them.

This series is intended to provide an introduction into the field of biblical textual criticism, but it cannot substitute for a master’s level university or seminary education on the science and art of textual criticism. It is there, under guided mentorship and practice, that the budding textual critic may learn this discipline with wisdom. Consider this to be an introductory online textbook to get our readers familiar with the discipline, which will be employed elsewhere on this site.

Introduction: What is Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible?

“Textual criticism is the science of discovering where a document has been corrupted, and the art of restoring it.”[1] When applied to the Hebrew Scriptures, this involves collecting and comparing many different Hebrew manuscripts with each other, while also keeping an eye on relevant ancient translations, such as those into Greek, Aramaic, and Latin. The purpose of this exercise is to determine, to the best of our knowledge, the correct text of the Hebrew Scriptures. Although it is easy to describe the goal of textual criticism, it is a complex procedure to perform.

As an example, consider an experiment where one hundred people are given their own photocopies of the American Declaration of Independence, and they are told to transcribe the words onto a sheet of paper with a pen. Once completed, everyone must turn in their transcriptions, and the photocopies will be discarded. Could an observer piece together the original wording of the Declaration with a good deal of reliability simply based upon the one hundred transcriptions? Common sense says that one probably could, although the procedure would not be so simple. Why? Because of the human factor.

Some people in our hypothetical experiment might have written with horrible handwriting that was nearly illegible. Others might have missed punctuation and capitalization. Others might have misunderstood the words they saw and misspelled them in their transcription. Some might have skipped lines in their transcription because they accidentally saw the same word on two lines. Some might not have been able to read the handwriting of the signatories, so they left out some of the names.

If we were to compare any individual transcription with another individual transcription, we might find only a handful of copies that actually agree perfectly with each other. Many of them would disagree with each other in multiple places.

How would one go about reconstructing the original text of the Declaration of Independence based on these hundred transcriptions? No cheating! We cannot look at the original—only the transcriptions. How would we accept certain spellings and punctuation marks, and not others? How would we identify outliers and come to any degree of confidence in our answers?

The answer to these questions is found in the science of textual criticism. It is the process by which we reconstruct the original text of documents using handwritten copies in our possession. In the case of the Declaration of Independence, we have the original signed copy of the text in the Washington D.C. National Archives. We do not need to do textual criticism to reconstruct this text, because we have the original. But in the case of the Hebrew Bible, we do not have the original manuscripts. We have copies of copies of copies of manuscripts. Each of the manuscripts differ from another in some way. We need textual criticism in order to piece together the original text to the best of our ability.

Unlike other forms of biblical criticism, textual criticism is nothing new. It is used to analyze all ancient works, not just the Bible, and it has been accepted (to varying degrees) by Jews and Christians as an attempt to determine the original text of God’s Holy Scriptures.

As Israeli textual scholar Emanuel Tov writes, “Since no single textual source contains what could be called the biblical text, a serious involvement in biblical studies necessitates the study of all sources, which necessarily involves study of the differences between them. The comparison and analysis of these textual differences thus holds a central place within textual criticism.”[2]

The Need for Textual Criticism

This article will not present a lengthy defense of why the Hebrew Scriptures have divine origin. However, if one does believe that the text is from heaven, then one should have motivation to protect the text through the process of textual criticism. Any community that looks to the Torah as divine needs to know what it says. It also needs to safeguard the text from intentional and unintentional errors that may have crept into the manuscript tradition. Thus, textual criticism is important to those who want to figure out exactly what Scripture says so that it may be believed and followed.

At Chosen People Answers, textual criticism is very important to us because we believe in the divine origin of the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings. Speaking from the standpoint of faith, these were not books that were created in the mind of men alone. The thoughts of the biblical authors—including their terminology, themes, and emphases—were inspired by God himself as they wrote. When the authors of these books took their pens to the manuscripts, their words were entirely perfect, holy, and without error. That original manuscript, penned by the authors, is called the “autograph,” since it is the one that was actually written upon by the author. Eventually, the autographs of the biblical books were compiled by faithful editors into the final form of the books we have in the Tanakh. It is these final forms that we are attempting to reconstruct in textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible.[3]

However, these final forms were eventually copied and made into daughter and granddaughter manuscripts, and along the way, some inadvertent or intentional changes were made. They deviated from the originals. These changes were not “inspired by God,” but were the deviations of men.[4] They were mistakes that sadly were sometimes copied and recopied to the point that the mistakes look like the correct version by sheer popularity. Unfortunately, we do not have any of the autographs or final manuscripts available, so we are reliant upon daughter manuscripts that may have mistakes within them.

Consequently, at Chosen People Answers, we begin with the assumption that no biblical manuscript is free from error, but that we should use all biblical manuscripts currently available to attempt a reconstruction of what the original text likely said. This process of textual criticism is science melded with faith: We seek a justifiable method to establish a trustworthy text so that we may better follow it and the divine author who inspired it. Consequently, the autograph in its final edited form, to the best of our understanding, is the infallible revelation from God, fully deserving of our faith and devotion.

There are some within the Jewish and Christian traditions who reject textual criticism as heretical. For example, you may have been taught, in line with Rambam, that the Torah we have today is perfect and inerrant. However, there are many examples of reasons why the manuscripts called the Masoretic Text, while amazingly accurate, still fall short of perfection. Once we compare two Hebrew manuscripts side by side, we find that it is intellectually untenable to believe that any single manuscript of the Tanakh is perfect and without error. We need textual criticism to weed out the errors in the manuscript tradition, so we can accurately read and interpret God’s holy Word.

In this section, we have endeavored to explain our motivation for participating in the science of textual criticism. We want to know what Scripture says, and what it does not say, because we believe it is true. However, for the rest of this article, we will not be addressing reasons why we should believe what the Scriptures teach; rather, we will address how we can know what the Scriptures teach. This is something that is important no matter what one’s faith tradition is.

Key Words in Textual Criticism

Textual criticism is a fascinating and complex field with its own terminology. In order to proceed in our basic introduction to textual criticism, we need to define some terms:

Apparatus

An apparatus is a scholarly work that contains a summary of textual variants (defined below) for the biblical text based on the manuscripts available up until the time of publication. For instance, an apparatus for the Masoretic Text will include all variants found in Hebrew manuscripts and from translations that have a different vorlage (defined below) than the Masoretic Text. An apparatus removes the need to physically consult the hundreds of manuscripts available for each biblical verse. If there is no data in the apparatus for a specific word or phrase, then it is assumed that there is no significant difference between Hebrew manuscripts and Greek and other versions.

Autograph

An autograph is the original manuscript written by the author of a work with his own hand or the hand of his scribe.

Codex

The codex is the earliest form of a modern book, consisting of multiple sheets of papyrus or vellum that are tied together on one side into a single compilation and enclosed within wooden bookends. The codex was the successor to the scroll, although it did not become prominent until the fourth century CE. The plural of codex is codices.

Emendation

An emendation is a scholarly conjectural solution (informed guess) to a textual problem. The emendation, or proposed restoration, to the missing text is not actually present in any textual witnesses (manuscripts). We must treat emendations with extreme caution, as they can be abused by those who do not respect the divine origin of the Tanakh.

Kethiv and Qere

Rabbinic scribes refused to alter the consonantal base text of the Hebrew Scriptures, even when they knew it was defective or not original. Instead of changing the text, they made a notation over the word and instructed the readers of Scripture during synagogue services to read the problematic word as something else. The written word was called Kethiv (Hebrew for “written”) and the spoken word was called Qere (Hebrew for “read”). This enabled the rabbinic scribes to fix a textual problem without actually changing the text.

Hexapla

The earliest example of extensive textual criticism of biblical manuscripts is the Christian scholar Origen’s massive Hexapla, compiled in the third century CE. This work compared the Jewish Bible in six versions, laid out in six columns: (1) Hebrew, (2) Hebrew transliterated into Greek letters, (3) Aquila’s Greek Version, (4) Symmachus’ Greek Version, (5) The Septuagint, (6) Theodotion’s Greek Version. Although the original work was lost during the Muslim invasions of Caesarea in the seventh century, Christian scribes preserved significant portions of the work in the margins of their biblical manuscripts. The standard critical edition of the Hexapla is by Frederick Field, available here.

Lacunae

A lacuna (pl. lacunae) is the technical term for a “hole” or a gap in a manuscript from which no text may be recovered. Most ancient manuscripts are only partial in content, and many have lacunae within their text, requiring researchers to “fill in the blanks” with their own conjectures, or emendations. Lacunae are indicated in transcriptions by putting [brackets] around conjectured text or carats (^) indicating missing letters.

Manuscript (MS)

A manuscript is any handwritten text of a specific work. A manuscript may refer to any material in which text is written: papyrus scrolls, vellum, codices, etc. The abbreviation for manuscript is MS, and the plural abbreviation is MSS.

Masoretic Text (MT)

The Masoretic Text is not a single text but rather a family of Hebrew manuscripts produced by the Masoretes between the years of 600 and roughly 1000 CE. These are the best-preserved manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible and they serve as the base text for modern Jewish and Christian translations. The Masoretic Text stabilized into something close to its medieval form around the first century CE (often called the Proto-Masoretic Text) and has been meticulously preserved by Jewish scribes since then. The Masoretic manuscripts we have today were produced primarily by the Ben Asher and Ben Naphtali families of Masoretes in Tiberias, and the best example of the Masoretes’ scribal quality is the Leningrad Codex (1009 CE).

Matres Lectionis

The Hebrew language does not have vowels included within the text, just like other ancient Near Eastern languages. The Masoretic Text as produced by the Masoretes includes vowel “pointings” above and below the consonantal text, but these marks were not original to the text. Originally, the Hebrew was in consonants only, but this led to difficulties in which certain words could be rendered with different vowels that were incorrect. During the Second Temple period (400 BCE – 70 CE), Jewish scribes sought to alleviate the problem by adding matres lectionis (literally, “Mothers of Reading”) to the consonantal text. This usually consisted of adding “primarily ה [h] = ‘a’ vowel, ו [w] = ‘o’ or ‘u’ vowels, and י [y] = ‘e’ or ‘i’ vowels.”[5] These helper letters are especially present in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and they assist the reader in correctly pronouncing the words.

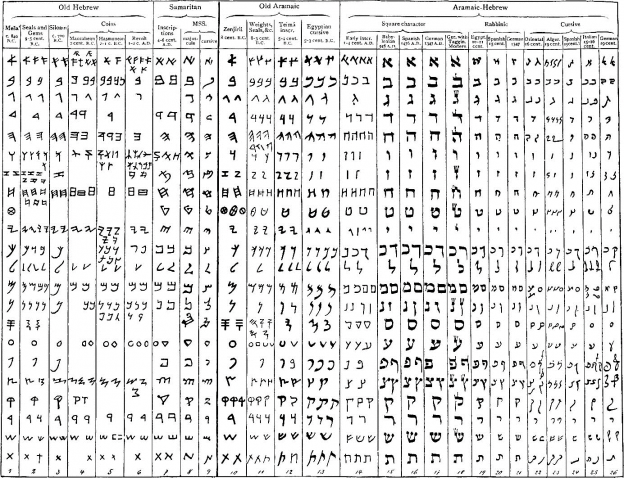

Paleo-Hebrew

Source: Eliyahu Yannai, City of David Archives, Creative Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paleo-Hebrew_seal.jpg

Today’s Hebrew is actually the “square script” of the Aramaic alphabet, which was adopted by Jewish people after the exile to Babylon. Before the exile to Babylon, Israel composed its texts in a script that is now called Paleo-Hebrew. This script did not have final ending letters and may or may not have been written with spaces between words. This is important, because our current Hebrew manuscripts were at some point copied from manuscripts written in the Paleo-Hebrew script. Bible scholar Paul D. Wegener writes, “Knowing about the similarities between specific letters in both paleo-Hebrew and square script can help identify and date certain copying mistakes. For example, the wāw and the yôd were very similar in the Hebrew square script written at Qumran, but they are not as similar in the paleo-Hebrew script.”[6] As an interesting sidenote, some of the Hebrew manuscripts at Qumran retained the reverential name of God in Paleo-Hebrew script, whereas the rest of the text was in our familiar square script. This ancient Jewish scribal practice did not survive in rabbinic Judaism.

Reading / Rendering

A reading or a rendering is the way a particular word is written in a particular textual witness. Two manuscripts can have identical readings, even if the languages are different. If the translation of one language into the other results in a similar word, then the readings are said to agree. The word rendering is sometimes used as a synonym for “translated as.”

Scroll

A scroll is an ancient form of a book in which a piece of papyrus, vellum, or animal hide is written upon and then rolled into a bundle. Most non-Jewish works transitioned from scrolls to the codex and the printed book, but this ancient form of writing continues to be the hallmark of Orthodox Judaism.

Textual Witness

A textual witness is any source that contains the purported text for a specific work. For example, a papyrus fragment that contains Genesis 1:1 through 2:5 (only) is a witness to the verses it contains. It is not a witness to Genesis 3:1. Textual witnesses may agree or disagree with other witnesses. Two witnesses for a specific text may be written in different languages.

Variant

When a textual witness disagrees with another textual witness, the difference in each witness is called a variant. For example, if one Hebrew manuscript has לא and another one has לו (as in Isaiah 9:2[3]), the two non-agreeing words are called variants. Variants may consist of individual letters, words, phrases, or entire sections. When investigating a text with witnesses in multiple languages, a difference is only called a variant when the vorlage of the languages disagrees.

Version

A version is a text of the Jewish Bible that is in a language other than Hebrew. The Septuagint is usually excluded from being defined as a “version” because of the unique importance of the translation. Versions are available in Greek, Latin, Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, and many other ancient languages.

Vorlage

Vorlage is a word coined by German scholars that means “that which lies before.” The vorlage is the reconstructed text of a source document that lies behind the text of a translated document. For example, we may have a text in Greek that was originally translated from Hebrew, but we do not have the Hebrew original available. The vorlage would consist of the Greek re-translated back into Hebrew. Oftentimes, the re-translation of a work back into Hebrew will uncover variants between the Masoretic Text and the vorlage. These variants may lead to further textual conclusions.

The collection of Jewish books called “the Bible” has come down to us in many different forms and languages. Some manuscripts are ancient, some are newer. Some are in Hebrew, some are in Greek, and some are in other languages. Some are even in an ancient form of Hebrew called Paleo-Hebrew. In this section, we will summarize the most important sources of the text of the Hebrew Bible.[7]

Primary Sources: Hebrew Manuscripts

As the original language of the Jewish Scriptures,[8] Hebrew is the most important textual language and the father of all daughter translations. An important rule of biblical textual criticism is that the Hebrew version of any text should always take precedence by default. Hebrew readings should only be overturned because of the presence of compelling evidence. Consequently, the following Hebrew manuscript sources are of utmost importance when considering the text of the Tanakh.

Masoretic Manuscripts

As defined above, the Masoretes were a community of Jewish scribes who meticulously preserved the Hebrew text and provided the world with the best transcriptions of the Hebrew text known today. Their manuscripts’ state of preservation is very high:

The meticulous efforts of the Masoretes and the Sopherim before them resulted in a marvelously successful preservation of the [Tanakh] text. What the Masoretes passed on to later centuries was meticulously copied by hand until the advent of the printing press. So it may be confidently asserted that, of ancient Near Eastern literature, the [Tanakh] is unique in the degree of accuracy of preservation.[9]

The manuscripts produced by the Masoretes have served as the definitive translation of the Hebrew Scriptures for both Jews and Christians. For example, the translation notes for the evangelical English Standard Version (ESV) speak of the Masoretic Text in high praise:

The currently renewed respect among Old Testament scholars for the Masoretic text is reflected in the ESV’s attempt, wherever possible, to translate difficult Hebrew passages as they stand in the Masoretic text rather than resorting to emendations or to finding an alternative reading in the ancient versions. In exceptional, difficult cases, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac Peshitta, the Latin Vulgate, and other sources were consulted to shed possible light on the text, or, if necessary, to support a divergence from the Masoretic text.[10]

In other words, these Christian translators believe the Masoretic Text is trustworthy, except in a few “exceptional, difficult cases” in which it helps to consult other versions.

Here are the most prominent members of the Masoretic Text family:

Leningrad Codex (1009 CE)

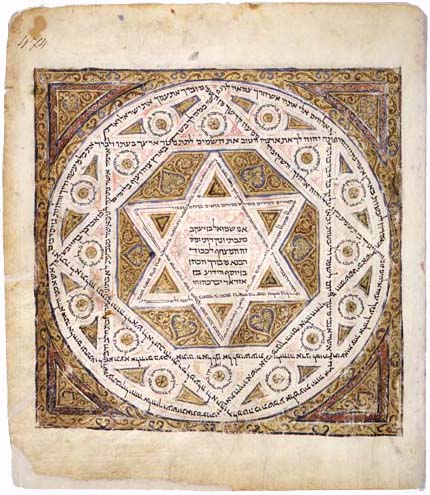

This magnificent codex is beyond question the most important Hebrew manuscript we have today. It is the oldest complete manuscript of the entire Tanakh, and it serves as the basis for most Hebrew Bibles and most Jewish and Christian translations today. The codex received its name from its place of residence in Leningrad, Russia (now known as St. Petersburg). It was produced by the Ben Asher family of Masoretes and is in excellent condition. A photographed copy of the Leningrad Codex is available digitally here.

Aleppo Codex (925 CE)

This Ben Asher Masoretic codex was captured by Crusaders in 1099, and then returned to the Jewish people, who took it to Cairo, Egypt. There it was consulted by Maimonides, who regarded it highly. The codex was eventually taken to Aleppo, Syria. It remained fully intact until 1948, when anti-Jewish riots caused a quarter of the codex to be destroyed by fire.[11] Today, the text of Genesis 1:1 through Deuteronomy 28:16 is missing, as well as assorted pages throughout the codex (i.e., Haggai, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, and Ezra are missing, and other books have only partial representation). The Aleppo Codex is the basis of the Hebrew University Bible Project, and the codex itself may be viewed online here.

Cairo Codex to the Prophets (895 CE)

The Cairo Codex to the Prophets was the product of the Ben Asher Masorete community. This work was also captured by the Crusaders in 1099 and returned to the Jewish people, who took it to Cairo for safekeeping. The codex today contains the Former and Latter Prophets (or, under the Christian designations, the Historical Books and the Prophets). This codex is very important because it is the earliest dated Masoretic manuscript.[12]

Other Masoretic Manuscripts

Libraries and museums around the world have many other manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible that were transcribed later than the previous three just mentioned. For example, Codex Reuchlinianus is dated to 1105 and includes the Prophets. The Erfurtensis Codices from the eleventh to fourteenth centuries contain the entire Hebrew Bible.[13]

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Jewish Encyclopedia gave a summary of all known Hebrew manuscripts up to that point.[14] It counted 165 manuscripts at the British Museum, 146 at Oxford, 32 at Cambridge, 102 in Paris’ National Library, 24 in Vienna’s Library, 39 at the Vatican, and assorted others. However, the total number of manuscripts is higher today due to new manuscript finds.

Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS, Third Century BCE–First Century CE)

The practice of textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible was revolutionized in 1947 with the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of Jewish manuscripts dating from the Second Temple Period. The approximately 800 manuscripts discovered in the Scrolls were mostly written in Hebrew (some in Greek) and consisted of Bible passages, Bible commentaries, and various sectarian works concerning the community that produced the manuscripts (probably the Essenes). These works are revolutionary because they give us manuscript versions of the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures that date from more than 2000 years ago. No longer are the Masoretic manuscripts the oldest Hebrew text we have of the Jewish Bible. Consequently, we can now compare these Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts with the medieval Masoretic manuscripts and look for explainable differences. This process often finds readings in which the Dead Sea Scrolls matches readings that were only known of previously in Greek and other versions of the Bible.

Samaritan Pentateuch (SP)

This version of the Hebrew Scriptures was known to the rabbis and the church fathers, but it passed into obscurity until the seventeenth century. The Samaritan Pentateuch is the official version of the Hebrew Bible used by the Samaritan community in Israel. The Samaritans trace their lineage back to the time of the first exile, when Gentiles from other nations were resettled into Israel by the Assyrians. These forced immigrants intermarried with local Hebrews, and ever since, the Samaritan community has fought accusations of being “half-breeds.” In any case, the Samaritans’ text is written in Paleo-Hebrew (the original script of the Hebrew Bible) and has many alterations within it to fit Samaritan theology. These alterations often show how trustworthy the Masoretic Text is, but sometimes the Samaritan Pentateuch agrees with the Greek Septuagint:

Of the 6,000 variants registered in comparison with the Masoretic text, 1,900 proved to be in accordance with the Septuagint. This can probably be attributed to their common dependence on an earlier source. Hence, although some of the Samaritan Pentateuch variants must be ascribed to a sectarian interpretation of the tradition, others must certainly derive from an ancient text tradition which was also known outside Samaritan circles. This opinion has been confirmed by biblical text fragments from Qumran which belong to the same text group.[15]

Bible scholars R. K. Harrison and J. E. Harry suggest how the use of the Samaritan Pentateuch can inform textual criticism:

While the Samaritan Pentateuch, when used in conjunction with the LXX, can furnish useful information in an attempt to restore an ‘original text,’ the readings of the Samaritan Pentateuch must be evaluated with great care if improvements upon the MT are being sought, since it tends in any case to demonstrate the purity of the MT. Most of all, the value of the Samaritan Pentateuch to the scholar is the manner in which it attests to the antiquity and textual integrity of the Torah.[16]

Other Hebrew Sources

The previously mentioned text sources include substantial portions of the Hebrew Bible. There are other sources of Hebrew text that are not as complete but are still important. For instance, the Nash Papyrus dates from about the second century BCE and includes the Ten Commandments and the Shema. Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, this was the oldest known Hebrew manuscript. Other sources of the Hebrew biblical text include the archaeological finds of amulets with Scriptural messages, but since these sources were often produced by untrained people for personal use, the value of these sources for textual criticism is slim.

Secondary Sources: Greek and Latin Translations of the Hebrew

Unlike modern Judaism today, ancient Jews made extensive use of the Greek language in religious life. For example, in Mishnah Megillah 1:8, Rabbi Gamaliel stated that the sacred Scripture should only be translated into Greek. However, in the centuries after the destruction of the Temple, most Jewish people discontinued use of the Greek, partially because of how the Jewish believers in Yeshua who wrote the New Testament had used the Greek version of the Bible to point to Yeshua. Consequently, the second century CE became a time of textual controversy over the language of the Scriptures. Three new versions of the Bible were produced in Greek during the second century, but this did not stop the controversy. The Jewish Encyclopedia summarizes the result:

As it became evident that the controversy could not be ended in this way, the Jews ceased to dispute with the Christians concerning the true religion, and forbade the study of Greek. They declared that the day on which the Bible had been translated into Greek was as fateful as that on which the golden calf had been worshiped (Soferim i.); that at the time when this translation was made darkness had come upon Egypt for three days (Ta‘an. 50b); and they appointed the 8th of Ṭebet as a fast-day in atonement for that offense. Not only was the study of the Greek Bible forbidden, but also the study of the Greek language and literature in general. After the war with Titus no Jew was allowed to permit his son to learn Greek (Soṭah ix. 14); the Palestinian teachers unhesitatingly sacrificed general culture in order to save their religion.[17]

In other words, in response to these controversies, Jewish people left Greek to the Gentiles, thereby cutting off the rich heritage that Jews had in the Greek language and in Greek Bible production.[18] Although Greek was left behind, textual scholars cannot do the same. Greek versions of the Hebrew Scriptures are very important for textual criticism because they were translated from ancient Hebrew manuscripts that we no longer have. By translating these Greek versions back into Hebrew, we can reconstruct a textual history that illuminates problematic passages in the Masoretic text.

Septuagint (LXX, third to second centuries BCE)

Pride of place for the Greek translations goes to the Septuagint, the first official translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. The origin of this work is shrouded in legend, but the ancient sources all claim that the Torah was translated during the time of King Ptolemy (third century BCE) by a group of 72 elders.[19] By rounding down to 70 and using Roman numerals, the Septuagint is often called the LXX. There is good evidence that the remaining books of the Tanakh (Nevi’im and Ketuvim) were translated by the second century BCE, and the collective work of Greek translations (Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim) during this era became known as the Septuagint.[20]

The Jewish people who produced the translation, however, had different translation philosophies. The translation tends to treat the Torah more literally, but other portions were so paraphrased that they were not reliable, such as in its translation of Daniel. But in any case, the Septuagint was the Bible used by millions of Jews for several centuries since the primary language of most Jewish people in this era was Greek. The Septuagint was used by Jewish historians, philosophers, and writers such as Philo, Josephus, the Dead Sea Scrolls community, and the authors of the New Testament.

In terms of textual criticism, the value of the Septuagint is remarkably high. The translators were working from a Hebrew manuscript that sometimes differed from the Masoretic text we know today. Sometimes the variants are supported by the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Samaritan Pentateuch, sometimes not. This gives us a window into the varied forms of the Hebrew Bible that existed within Judaism before the text was standardized around the first century CE. In the Encyclopedia of Judaism, Paul Flesher discusses this dynamic:

Given its age, the reasoning goes, the Septuagint’s text is much closer in time to the period during which the books of the Hebrew Bible were composed, and it is thus more likely to give an accurate picture of the original biblical text. But the fact that the Septuagint’s age makes it possible for it to be accurate does not mean that it necessary is. It could equally be based on an early but corrupt manuscript or simply be a poor translation. Accordingly, it is only in comparison with other versions and manuscripts that the Septuagint can really be used. Much of the time, it agrees with the Masoretic text, and so supports its accuracy. Other times, it disagrees with it while agreeing with other ancient texts, such as the biblical manuscripts found at Qumran. This is the case, for instance, where the Septuagint agrees with the Qumran fragments of Samuel against the Masoretic text, suggesting that they preserve an earlier reading. Qumran fragments of other biblical books, however, show closer affinity with the Masoretic text than with the Septuagint. The Septuagint thus cannot be simply assumed to reveal an earlier, and therefore more accurate, version of the Bible.[21]

The LXX is important for textual criticism of the Hebrew Scriptures in its own right, but it is also important because it is the only translation of the Hebrew Bible before the advent of Christianity. As such, the LXX has a lack of bias toward or against belief in Jesus, which is helpful when attempting to discuss passages that have become controversial since the teachings of Jesus and his followers.

Consequently, the LXX is extremely important for believers in Jesus. The authors of the New Testament often quoted from the Septuagint when citing Scripture. Some people attack the New Testament for its quotations of Old Testament texts, claiming that the apostles tampered with the holy Hebrew text. However, the truth is often that the New Testament quoted from the Septuagint, a valid Jewish translation, rather than the Masoretic, another valid Jewish source.

Aquila (second century CE)

By the second century CE, the Septuagint had been the widely accepted translation of the Bible for Jewish people for centuries, including the Jews who believed in Jesus. When these Jewish believers started appealing to the Septuagint to explain their faith in Jesus, some Jewish religious leaders sought to distance themselves from the popular LXX translation. They embarked on this separation by commissioning a proselyte named Aquila to produce a new Greek translation (y. Megillah 71c). This translation attempted to be literal to the Hebrew text and to retranslate passages that the New Testament appealed to for Messianic evidence (like Isaiah 7:14).[22]

Aquila’s translation does not survive in any manuscript form. Jewish people quickly abandoned it, and followers of Jesus rarely used it. However, in the third century CE, the church father Origen produced his Hexapla, which placed six versions of the Scriptures side by side for comparison. One of the versions was Aquila’s. Unfortunately, even Origen’s work was lost in the seventh century CE, but Christian scribes preserved many of Aquila’s passages in the margins of other Greek Bible manuscripts. Frederick Field compiled these renderings in his edition of the Hexapla, which continues to be the standard edition, despite its 1875 date of publication. Thus, despite not having any manuscripts from Aquila, we still have many examples of Aquila’s translation available to us today.

Theodotion (mid–late second century CE)

The identification of the translator behind Theodotion’s version is unclear, but ancient church sources claim he was of Jewish background.[23] His translation attempts to correct the Septuagint and bring it closer to the Hebrew manuscripts then available. His translation of the book of Daniel was accepted by churches quite early because of the major problems with the Septuagint version of that book. Theodotion’s version attempts to translate the Hebrew literally, but not as much as Aquila’s. Like Aquila’s version, the principal evidence for this translation was in Origen’s Hexapla, which can be consulted in Field’s reconstruction.

Symmachus (circa 200 CE)

Symmachus produced his translation around 200 CE, and all ancient sources describe him as Jewish, although they disagree on what religious affiliation he had.[24] His translation attempts to be faithful to the Hebrew text while taking liberties to ensure that the Greek flowed naturally with literary style. As such, it could be usable by Greek speakers who knew no Hebrew, which was not the case with Aquila’s version. Like Aquila and Theodotion’s translations, Symmachus’ version only survives in the Hexapla, which is accessible in Field’s editon here.

Quotations in Second Temple Jewish Sources

Other sources of the Greek text of Scripture may be found in the plentiful quotations of Scripture found in the New Testament, the works of Philo, the works of Josephus, and the apocryphal and pseudepigraphical works produced by Jews of the Second Temple Period (third century BCE through first century CE). More often than not, the underlying text in these sources comes from the Septuagint.

The Latin Vulgate (fifth century CE)

In the fifth century CE, the church father Jerome surveyed the Latin versions of the Bible being used by Western churches and found them to be woefully inadequate. While living as a monk in Syria, he learned biblical Hebrew under the teaching of a Jewish believer in Jesus.[25] Years later, he was commissioned to translate the Scriptures into a new Latin translation, so he moved to Bethlehem and studied Hebrew under the tutelage of multiple Jewish scholars. His translation was based upon Hebrew manuscripts available in the fifth century, of which we have none today. Consequently, the Vulgate is an excellent source for what the Hebrew said during Jerome’s time, if one retranslates Jerome’s Latin to the Hebrew vorlage he consulted.

Tertiary Sources: Ancient Versions

The third class of sources here were translated after the split of Christianity and Judaism, and they often were translated without consulting a Hebrew source. Their distance from the Hebrew is considerably further from the previous sources listed and must be used in textual criticism with caution.

Syriac Peshitta (circa 200 CE)

Our knowledge of this translation of the Hebrew Bible into Syriac (a version of Aramaic) is limited. The Eastern Syriac-speaking church eventually used this version, but most scholars do not think it originated with them. It was probably the product of a non-rabbinic Jewish group around the year 200 CE, which based its translation upon the Greek. Textual scholar Paul Wegner writes,

The Syriac Peshitta is important for textual criticism because it is a fairly early version of the Old Testament from a separate Jewish tradition, and if the earlier stage [of its production] can be determined, it provides significant evidence for the MT text. However, the later stages of the Peshitta text have been modified to bring it into closer harmony with the LXX and are therefore less helpful for Old Testament textual criticism.[26]

Targums

The Targums are paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible produced in the Aramaic language, the language used by many Jews from the first century CE onward. They are not meant to be literal renderings of the Hebrew, but rather expansionary works for corporate learning and devotion. Some Targums have rabbinic teachings and interpretations included directly in the text. They change words to suit rabbinic theological emphases. Consequently, the use of the Targums in textual criticism is somewhat limited.

Daughter Translations of Septuagint in World Languages

Jesus famously told his disciples to go and make disciples among all the Gentiles (Matt. 28:19), and Jesus’ Jewish followers took that commission seriously. They started traveling around the known world, preaching the message of the Scriptures. However, they went to far-off places with foreign languages that had no Bible translation. The Septuagint was available for Greek speakers, but not all their audiences spoke Greek. Consequently, over the next few centuries, Jesus’ followers began translating the Bible into other languages, often using the Greek Septuagint as the parent text. Some of the translations include Slavonic, Gothic, Georgian, Bohairic, Sahidic, and Ethiopic versions of the Old Testament.[27] Later, versions in Arabic and Coptic were produced. Each of these translations has a fascinating literary history, but their use in textual criticism is limited because many are two translations away from the original Hebrew text.

How to Find What The Different Sources Say

The complexity of the quest to determine the best readings of Scripture presents a very high barrier to entry. Familiarity with multiple languages is required, as well as the knowledge of a historian and the problem-solving of a detective. These things can only come with practice, study, and hard work. But there is an even more basic problem: How do we find what the different versions of Scripture say?

In previous eras, consulting a half-dozen versions of Scripture would require access to the library of a great theological institution or a national museum, plus the credentials to get access to the manuscripts themselves. With the advent of photography and the digital revolution, now anyone can consult the manuscripts from their own computer. Nearly all of the resources mentioned below are available in paper book form as well as digitally on a computer or mobile device. Many are available for free.

Standard Critical Editions

Each of the original sources listed in the “Text Families” section have “critical editions” of their texts. A critical edition is an edition of a manuscript source produced by scholars with an associated apparatus that contains information about textual variants. Critical editions can come in two flavors:

Here are the most important standard critical editions of the Hebrew Bible, listed by source:

| Source Text | Critical Edition | Edition Type |

| Masoretic Text | Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) | Diplomatic |

| Dead Sea Scrolls | Discoveries in the Judaean Desert Series | Diplomatic |

| Septuagint | Göttingen Septuagint | Eclectic |

| Samaritan Pentateuch | Der hebraische Pentateuch der Samaritaner by A.Freiherr von Gall | Eclectic |

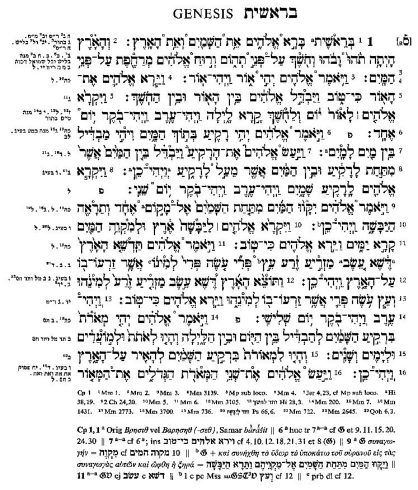

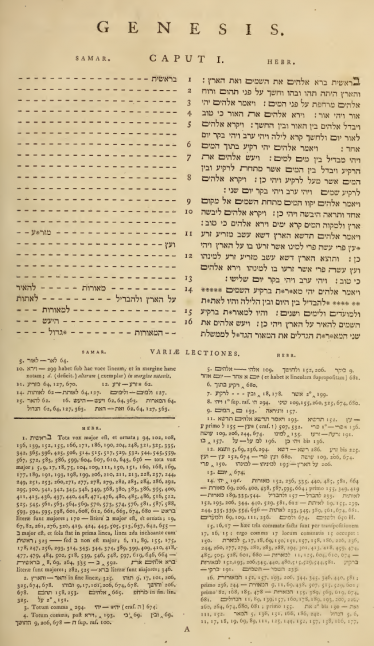

One work stands out above the others as the standard resource for textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible. At the current time, the most complete critical edition of the Hebrew Bible is the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). This work is based upon the Leningrad Codex, so the entire Hebrew Bible is included. It includes major textual variants from all the other sources, including the Dead Sea Scrolls. New discoveries have been made since the BHS was published in 1977, so it is not up to date in the textual evidence it provides. For those wanting the cutting-edge of research, the revised edition of the BHS is called Biblia Hebraica Quinta, but it is still in the process of production as of our writing. In the meantime, BHS remains the best resource for the complete Masoretic Text. A page of the BHS looks like this:

For textual criticism, the most important section of the page is the block of text at the bottom, which is the apparatus. To the right of “Cp 1, 1,” (lower left corner) which means “Chapter 1, Verse 1,” there is an “a” that corresponds to the “a” after בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית in Genesis 1:1. The note says “Orig Βρησιθ vel Βαρησηθ (-σεθ),” which contains an acronym and Greek and Latin all together! Yes, textual criticism can be quite cryptic! This note is shorthand for, “In Origen’s Hexapla, the column with Hebrew transliterated into Greek contains three ways to render this word: Bareysith, Bareyseyth, and Bareyseth.” In other words, we don’t know exactly how the Hebrew word was pronounced in the third century CE (Origen’s time), but it was something close to these three ways of saying the word. A trained linguist would recognize that the only thing that is variable between the three Greek renderings is the vowel pronunciation, meaning that the consonantal Hebrew text (in this case, בראשית) is consistent and secure.[28]

Free Internet Sources of Primary Documents

If a budding textual critic were to get started in textual criticism at low cost, then a printed copy of BHS and internet access would be the place to start. With the BHS as a starting point, the textual critic can go to various free internet sites to research other sources.

Here are some recommendations:

| Masoretic Text | Many websites and software packages have the Masoretic Text available, including here on Biblia.com. The text is derived from Westminster Theological Seminary’s digitization of the Leningrad Codex, which has become the standard digital version of the Tanakh.

The Leningrad Codex is available for reading in facsimile form here.

The Aleppo Codex is available for reading in facsimile form here. |

| Dead Sea Scrolls | To read the handwritten Hebrew script of first-century Bible scrolls, go to The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

The Israel Museum has a few scrolls available, most notably the Great Isaiah Scroll.

Transcriptions and translations of the Dead Sea Scrolls that are reliable are available only by purchase, but if absolutely necessary you can use the free transcriptions found on this site at your own risk. |

| Septuagint | The Rahlfs edition of the Septuagint is an eclectic edition that is available at Blue Letter Bible.

If you do not know Greek, you can consult the free (but older) Brenton English translation of the Septuagint, available here. |

| Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus | As mentioned before, the only source for these translations is a reconstructed Hexapla, which is available by Frederick Field here. |

| Other Sources | The Vulgate is available on LatinVulgate.com. It includes an English translation.

The Syriac Peshitta of the Jewish Bible is available here.

Many Targum texts are available on the Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon site. Several English translations are listed at Targum.info. |

Paid Digital Programs

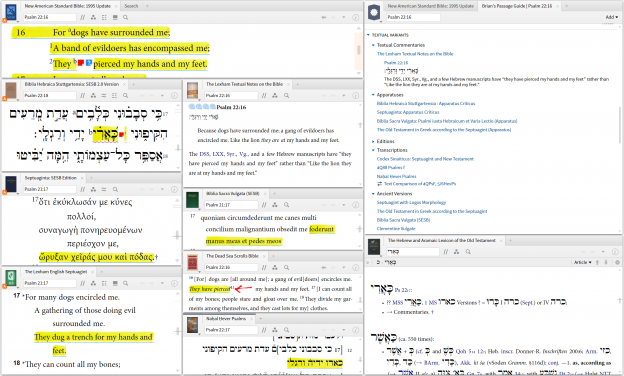

Although there are many free resources available on the internet, and many excellent paper versions of critical sources, there is nothing like the power and flexibility of a scholarly Bible study program. At Chosen People Answers, we do not usually consult paper books for textual criticism, and we rarely use any of the internet sources listed above.

Instead, we use Logos Bible Software and the multitude of scholarly text-critical sources available within the platform. On a single screen, we can display multiple versions of the Hebrew Bible, synced to scroll with one another, alongside textual apparatuses and other books that discuss textual variants. Here is an example of having multiple resources all looking at the controversial textual variant on Psalm 22:16:

Kennicott’s Collection of Hebrew Variants

There are hundreds of Hebrew manuscripts in existence from before the advent of the printing press. Although the BHS provides a good selection of the most important Hebrew variants, it is selective in which variants it lists in its apparatus. If one wants to see a nearly exhaustive list of Hebrew textual variants, such a list does not exist. However, we can approach an exhaustive list through the work of eighteenth-century Hebrew scholar Benjamin Kennicott. Although his work Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum com Variis Lectionibus is now hundreds of years old, it remains the most complete summation of the variants in the Hebrew manuscript tradition.[29] It is available online for free here.

Although much of Kennicott’s work is in Latin, enough of it is in Hebrew that it may be somewhat usable without knowledge of Latin. Kennicott’s contemporary, Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi, produced a similar work of scholarship on Hebrew variants, Variae Lectiones Veteris Testamenti, available here, but it is so dependent upon Latin knowledge that it presents a higher barrier to entry.[30]

It is no longer necessary to travel to the far corners of the earth and sit in libraries, museums, and monasteries to consult the primary witnesses to the text of Scripture. Now it is right at our fingertips, even on our smartphones. It is an exciting time for the budding textual scholar.

Bibliography

Anderson, Amy, and Wendy Widder. Textual Criticism of the Bible. Edited by Douglas Mangum. Revised Edition. Vol. 1. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018.

Bromiley, Geoffrey William. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. 4 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988.

De Rossi, Giovanni Bernardo. Variae Lectiones Veteris Testamenti. 4 vols. Parmae Regia Typographia, 1788. http://archive.org/details/VariaeLectiones.

Elwell, Walter A, and Barry J Beitzel. Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1988.

Flesher, Paul V. M. “Privileged Translations of Scripture.” In The Encyclopaedia of Judaism, edited by Jacob Neusner, Alan J. Avery-Peck, and William Scott Green, 3:1309–20. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2000.

Kennicott, Benjamin. Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum : cum variis lectionibus. 2 vols. Oxford, UK: Typographeo Clarendoniana, 1776. http://archive.org/details/vetustestamentum01kenn.

Müller, Mogens. The First Bible of the Church: A Plea for the Septuagint. Vol. 206. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996.

Singer, Isidore, ed. The Jewish Encyclopedia. 12 vols. New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1901–1906.

Skarsaune, Oskar. “Evidence for Jewish Believers in Greek and Latin Patristic Literature.” In Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries, edited by Oskar Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007.

Tov, Emanuel. “Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, Methodology.” In The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Magnum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Vanhoozer, Kevin J., Craig G. Bartholomew, Daniel J. Treier, and N. T. Wright, eds. Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014. http://www.credoreference.com/book/bpgtib.

Wegner, Paul D. A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods & Results. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006.

Wonneberger, Reinhard. Understanding BHS: A Manual for the Users of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 2nd rev. ed. Vol. 8. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 1990.

Footnotes

- Kevin J. Vanhoozer et al., eds., Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014), 784, http://www.credoreference.com/book/bpgtib. ↑

- Emanuel Tov, “Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, Methodology,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. John D. Barry et al. (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016). ↑

- For example, Moses wrote the Torah, but we do not believe he wrote the final verses of Deuteronomy, which describe his death. The final version of Deuteronomy included the final verses, added by an unknown editor. These final verses are just as “inspired” as the verses authored by Moses. A textual reconstruction of the “final form” of Deuteronomy would include the final verses, not just the ones that came from Moses’ hand. ↑

- For example, the Samaritan Pentateuch is mostly the same as the Masoretic Text, except that it repeatedly describes Mount Gerizim as the authorized location for worship. Through the process of textual criticism, we can see that this is not what Moses originally wrote. The Samaritan Pentateuch deviates from the original meaning of Scripture in these locations. ↑

- Paul D. Wegner, A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods & Results (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 35. ↑

- Paul D. Wegner, A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods & Results (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 60. ↑

- For a handling of this topic in a major Jewish publication, see Paul V. M. Flesher, “Privileged Translations of Scripture,” in The Encyclopaedia of Judaism, ed. Jacob Neusner, Alan J. Avery-Peck, and William Scott Green (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2000). ↑

- Except the Aramaic portions of Daniel and Ezra/Nehemiah. ↑

- . Walter A Elwell and Barry J Beitzel, Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1988), s.v. Masora, Masoretes. ↑

- “Preface to the English Standard Version,” ESV.org, accessed July 17, 2019, https://www.esv.org/preface ↑

- Amy Anderson and Wendy Widder, Textual Criticism of the Bible, ed. Douglas Mangum, Revised Edition, vol. 1 (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018), 64–65. ↑

- Anderson and Widder, 1:65–66. ↑

- Wegner, Student’s Guide, 160–61. ↑

- Isidore Singer, ed., The Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1901–1906), s.v. Bible Manuscripts. ↑

- Mogens Müller, The First Bible of the Church: A Plea for the Septuagint, vol. 206 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996), 35–36. ↑

- Geoffrey William Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988), s.v. Pentateuch, Samaritan. ↑

- Singer, The Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. Greek Versions of the Bible. ↑

- This dynamic was not the case for the Greek-speaking Jews living in the Byzantine Empire. They continued speaking Greek for centuries. ↑

- Hence the reason why the translation is called the Septuagint, or LXX, which means “70.” ↑

- We discuss the range of evidence in this article: “Was the Greek Septuagint Twisted by Christians to Prove Jesus?” However, the introduction to the apocryphal book of Sirach, dated to the mid-second century BCE, provides an example of strong evidence. It refers to translations of the entire Hebrew Bible into Greek. ↑

- Flesher, “Privileged Translations of Scripture.” ↑

- For an extensive survey, see Singer, The Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. Aquila. ↑

- Irenaeus, Adv. Haer. 3.21.1, Jerome, De viris illustr. 54. ↑

- Church father Epiphanius of Salamis claimed he was a Samaritan convert to Judaism (Weights and Measures 16). Church historian Eusebius (Hist. eccl. 6.17) said he was a Jewish Ebionite. ↑

- Jerome, Letter 125.11, Oskar Skarsaune, “Evidence for Jewish Believers in Greek and Latin Patristic Literature,” in Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries, ed. Oskar Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007), 541. ↑

- Wegner, Student’s Guide, 274. ↑

- Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, s.v. Versions. ↑

- For more detail about how to use the BHS for textual criticism, consult this primer: Reinhard Wonneberger, Understanding BHS: A Manual for the Users of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, 2nd rev. ed., vol. 8 (Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 1990). ↑

- Benjamin Kennicott, Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum : cum variis lectionibus, 2 vols. (Oxford, UK: Typographeo Clarendoniana, 1776), http://archive.org/details/vetustestamentum01kenn. ↑

- Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi, Variae Lectiones Veteris Testamenti, 4 vols. (Parmae Regia Typographia, 1788), http://archive.org/details/VariaeLectiones. ↑

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.