In this article, we will summarize some general procedures in textual criticism and demonstrate methods that are helpful in identifying (and correcting) problems in the biblical manuscripts. The end goal is to have a clearer understanding of what is contained within the Holy Scriptures, so that we may better follow the God of Israel who inspired them.

This series is intended to provide an introduction into the field of biblical textual criticism, but it cannot substitute for a master’s level university or seminary education on the science and art of textual criticism. It is there, under guided mentorship and practice, that the budding textual critic may learn this discipline with wisdom. Consider this to be an introductory online textbook to get our readers familiar with the discipline, which will be employed elsewhere on this site.

The Kinds of Problems in Manuscripts

As mentioned in Textual Criticism 101, no copy of a manuscript is immune from human errors during the copying process. Scribes can go to great lengths to ensure a trustworthy copy, and their efforts must be commended, but even so, perfect copies were impossible before the advent of photography and the digital revolution. In this section, we will highlight some of the common mistakes found in manuscripts.[1] Textual scholar Emanuel Tov gives some examples of the kinds of things that could go wrong:

The number of factors that could have created corruptions is large: the transition from the early Hebrew to the square script, unclear handwriting, unevenness in the surface of the leather or papyrus, graphically similar letters which were often confused, the lack of vocalization, unclear boundaries between words in early texts leading to wrong word divisions, scribal corrections not understood by the next generation of scribes, etc.[2]

Let’s look at some of the major textual mistakes under the categories of omissions, additions, misspellings, and intentional changes.

Omissions

Omissions occur when the parent manuscript has a text that a daughter manuscript neglects to include. Some common forms of omissions are haplography and parablepsis.

Haplography

This is the omission of a letter or a word due to a similar letter or word occurring close by. A copyist’s eye could skip from one letter to another without realizing his mistake. An example of this in the Masoretic Text is in Judges 20:13, where the copyist omitted בְּנֵי (b’nei, “sons of”) just before בִנְיָמִן (Binyamin, “Benjamin”) because the omitted word has the same spelling as the beginning of “Benjamin.” The Masoretes recognized this mistake and left the vowel pointings for בני in the text, without including the missing consonants.

Parablepsis

This term, which means “faulty seeing,” is when a scribe is careless in following his text and leaves out text between two similar words. For example, we can compare 1 Kings 8:16 with its parallel in 2 Chronicles 6:5–6 and see that 1 Kings has no text that lies between two occurrences of the word שָׁם in 2 Chronicles:

1 Kings 8:16 (Leningrad Codex)

מִן־הַיֹּ֗ום אֲשֶׁ֨ר הֹוצֵ֜אתִי אֶת־עַמִּ֣י אֶת־יִשְׂרָאֵל֮ מִמִּצְרַיִם֒ לֹֽא־בָחַ֣רְתִּי בְעִ֗יר מִכֹּל֙ שִׁבְטֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל לִבְנֹ֣ות בַּ֔יִת לִהְיֹ֥ות שְׁמִ֖י שָׁ֑ם וָאֶבְחַ֣ר בְּדָוִ֔ד לִֽהְיֹ֖ות עַל־עַמִּ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

2 Chronicles 6:5–6 (Leningrad Codex)

מִן־הַיֹּ֗ום אֲשֶׁ֨ר הֹוצֵ֣אתִי אֶת־עַמִּי֮ מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַיִם֒ לֹא־בָחַ֣רְתִּֽי בְעִ֗יר מִכֹּל֙ שִׁבְטֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל לִבְנֹ֣ות בַּ֔יִת לִהְיֹ֥ות שְׁמִ֖י שָׁ֑ם וְלֹא־בָחַ֣רְתִּֽי בְאִ֔ישׁ לִהְיֹ֥ות נָגִ֖יד עַל־עַמִּ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃ וָאֶבְחַר֙ בִּיר֣וּשָׁלִַ֔ם לִהְיֹ֥ות שְׁמִ֖י שָׁ֑ם וָאֶבְחַ֣ר בְּדָוִ֔יד לִהְיֹ֖ות עַל־עַמִּ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

One way to explain this is that the scribe saw one שָׁם, wrote it on his parchment, accidentally looked back at the second שָׁם, and continued his transcription. Another example of this is 1 Samuel 14:41. The Masoretic Text omits several lines of text found in the Septuagint and Vulgate likely because of the presence of the word “Israel” at the beginning and end of the omission.

Additions

Additions occur when the parent manuscript does not have a text that a daughter manuscript adds for some reason or another. Some common forms of additions are:

Dittography

This is the erroneous duplication of a letter, syllable, or word. One example of this in the Masoretic Text is in Jeremiah 51:3, where the word ידרך (yidroch, “draw”) appears in the text twice. The Septuagint, Targums, Peshitta, and Vulgate do not include the repeat word.

Conflation

A conflation is when a scribe has two textual traditions in front of him, and instead of choosing between one or the other, he combines the two into a single reading. For example, in the Masoretic Text of 2 Samuel 22:38–39, David says of his enemies, “Neither did I turn back till they were consumed. And I have consumed them” (JPS 1917). The Hebrew reads עד כלותם ואכלם. However, this is a conflated reading of two previous textual traditions. The Septuagint only has the second phrase: “I consumed them,” which would have been עד אכלם in Hebrew. The Dead Sea Scroll 4Q51 only has “Until they were consumed,” or עד כלותם. The Masoretic scribe may have seen both of these versions in front of him and decided to include both forms of the verb in his transcription.[3]

Glosses

A gloss is a short addition to a text that helps contemporary readers understand what is discussed. Glosses probably originated in the margins of biblical texts and were eventually included within the text itself. Two examples of this are present in all our versions of Genesis 14. In Genesis 14:3, the text says that Abram’s opponents gathered in “the valley of Siddim (that is, the Salt Sea).” The scribe perceived that the name of “Siddim” was an archaic designation that his readers would be unfamiliar with, so he added the parenthetical explanation. Later, in Genesis 14:14, our versions say that Abram pursued his opponents “as far as Dan.” However, the region belonging to the Tribe of Dan was not named “Dan” until hundreds of years after Abram, after Joshua’s conquest of Canaan. The scribe wanted his readers to be familiar with the places that Abram conducted his affairs, so he updated the location name to the common usage of “Dan.”

Misspellings

Metathesis

Metathesis is when a scribe accidentally reverses the order of two letters or words. This is most difficult to detect when the reversal still makes grammatical and rational sense. However, it can be detected when comparing various manuscripts to each other. A good example is in Deuteronomy 31:1, in which the Masoretic Text reads וַיֵּלֶךְ מֹשֶׁה (vayelech Moshe, “and Moses went”), whereas the Dead Sea Scroll 4QDtn makes more sense with ויכל משׁה (vayechal Moshe, “and Moses finished”). The only difference between the two renderings is the swapping of two letters.

Fusion

Fusion is when two words that are supposed to be separate are combined into one, changing the meaning of the passage. A good example of this is in Leviticus 16:8, where the Masoretic Text says that a lot is cast “for Azazel” (לַעֲזָאזֵל) on the Day of Atonement. The Mishnah has an early tradition of reading the text in this way (m. Kippurim 6:1). However, the even earlier Septuagint reads the passage as “for the goat of departure,” (τῷ ἀποπομπαίῳ) or in other words, “for the scapegoat.” This fits the context of the passage and makes sense. This rendering in the Septuagint derived from seeing two words (לָעֵז אֹזֵל) whereas the Mishnah and Masoretic Text saw only one (לַעֲזָאזֵל). Instead of speculating that this Azazel is a “most mysterious extrahuman character” as in Jewish folklore,[4] we should see this as a place where a simple scribal fusion combined two words in the Masoretic tradition.

Fission

Fission is when a word is incorrectly split into two, resulting in a difference of meaning. This is easy to do with letters such as כ and מ that can be added to a following word as a prefix. Fission is especially prone to happening since ancient paleo-Hebrew did not have final forms of letters and was often written without spaces between words. One example of this is in Hosea 6:5, in which the Masoretic Text has split two words incorrectly. The Masoretic has וּמִשְׁפָּטֶיךָ אֹור יֵצֵא (“and your judgments, light goes forth”), which is grammatically and contextually awkward. The Septuagint, in contrast, has “My judgment will go out like light,” which makes much more sense. All this took was for the final kaf (ך) attached to “judgments” to instead be attached (כ) to the next word, “light.”

Mistaken Letters

There are several letters in both Aramaic-script Hebrew (“square script”) and in ancient paleo-Hebrew that look alike and can be easily mistaken for one another. In the common square script, the dalet and resh look similar (ד and ר, respectively). There are several places in the Masoretic Text where these letters seem to be mistaken for each other. For example, in Genesis 10:4, the majority of Hebrew manuscripts have דֹדָנִים (Dodanim), but some have רֹדָנִים (Rodanim). The minority reading (Rodanim) is also attested in the Greek Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch, and Josephus. The problem is compounded because 1 Chronicles 1:7 refers to Genesis 10:4 and uses the word רֹודָנִֽים (Rodanim) in many manuscripts. Thus, many ancient sources and several Hebrew manuscripts for Genesis and many Hebrew manuscripts for 1 Chronicles have a different letter than is given in most editions of Genesis. This was likely a simple mistake of an ancient scribe reading the letters incorrectly, and the non-Masoretic rendering of רֹדָנִים (Rodanim) is likely correct in both Genesis and Chronicles.

Homophony

Some scribal schools copied their manuscripts by having a reader dictate a text, and the scribes listened and wrote what they heard. This was an efficient way to produce multiple copies quickly, but it also led to the problem of homophony, which is the mistaking of words that sound similar to each other. Several Hebrew letters sound like each other or are unpronounced (ת and ט, ס and שׂ, א and ע, ק and כ) and may be mistaken for each other by ear. One example of this is in Isaiah 9:2.[5] The Masoretic says that God “has not (לֹא) increased the joy,” which does not fit the context of the passage. The Qere (oral) reading for this word is the more appropriate לוֹ (“to him/it”), which sounds exactly the same. This rendering is attested in Targum Jonathan and the Peshitta.

Intentional Changes

All the changes described up to this point have been the result of unintentional mistakes made by scribes in the copying process. But the process of textual criticism also uncovers intentional changes. Wegner writes,

Generally it is easier to spot an unintentional change—they are a more predictable result of the copying process. An intentional error, on the other hand, is much more difficult to determine. Bruce Metzger observes, “scribes who thought were more dangerous than those who wished merely to be faithful in copying what lay before them.” Intentional errors are much harder to detect and correct since it is generally difficult to know why the changes were made.[6]

Below are some examples of intentional changes we find in the textual tradition of the Hebrew Scriptures.

Spelling Differences

A language only stops changing when it ceases to be used by a live society of people. A living language will morph over time through the simple process of being used. Two of the ways languages change is through spelling and grammar changes. For example, in American English we have theater, but in Great Britain it is theatre. Color and colour, you all and y’all. The same thing happened in Hebrew throughout the centuries. Hebrew scribes sometimes chose to add letters to the consonantal text called matres lectionis so words could be more easily identified—an early attempt similar to the Masoretes’ vowel pointing system. For example, in Isaiah 53:5, the Dead Sea Scroll 1QIsaa has מעוונותינו whereas the MT has מֵעֲוֹנֹתֵינוּ. The only difference is that the Dead Sea Scroll adds a vav (ו) to indicate a holem vowel sound. As in this example, these changes rarely change the meaning of the passage, only the spelling.

Harmonization

Harmonization is when a scribe decides to change the text to make it more agreeable to the overall context, thereby “improving” upon the text. One example of this is in the Septuagint in Genesis 1:8. In the creation story, it is usually repeated, “And God saw that it was good,” but this text is not present in any witness for the second day (Genesis 1:8) except in the Septuagint. The translators of the Septuagint may have been perplexed about the omission of “It was good” from the verse, so they added it in to fit the context.

Euphemistic Changes

Sometimes scribes were embarrassed by the text of Scripture and decided to change it to something they deemed more appropriate. Wegner gives some examples of how parallel passages between Samuel and Chronicles show that scribes were unwilling to write the name of the false god Baal, and instead substituted the name with something that took a jab at him:

The divine name בַּעַל (baʿal, “Baal”) was sometimes replaced with the word בֹּשֶׁת (bōšet, “shame”; 1 Chron 8:33; 9:39: אֶשְׁבָּעַל [ʾešbāʿal, “man of Baal”; compare the parallel verses in 2 Sam 2:8–12: אִישׁ־בֹּשֶׁת [ʾîšbōšet, “man of shame”]; 1 Chron 8:34; 9:40: מְרִיב בָּעַל [mĕrîb bāʿal, “Baal is (my/our) advocate(?)”] = 2 Sam 4:4: מְפִיבֹשֶׁת [mĕpîbōšet, “from before shame”]). A plausible explanation for this change is that the Baal cult posed a significant active threat to [Judaism] when the books of Samuel were written, so the author substituted a euphemism for the offensive name Baal. By the Chronicler’s time, however, the Baal cult had become less of a threat and he was able to employ the name.[7]

Tiqqune Sopherim – Theological Changes

Sometimes scribes made intentional changes because they wanted to keep the text from being misunderstood in a heretical fashion. The Masorah, which is the system of marginal notations in Masoretic manuscripts, indicates at least 18 places where the scribes made changes to the text in this way. One example of the changes reported is in Genesis 18:22, where the Masoretic text says, “Abraham remained standing before the Lord” (NJPS). However, the Masorah says that this is an example of the “corrections of the scribes” (tiqqune sopherim) because the original Hebrew text said, “the Lord remained standing before Abraham.” This was seen as irreverent, since it was thought that the Lord would stand before only someone in higher rank than him, or could not stand at all (since God does not have a body). The scribes decided to reverse the order of the subjects so it would fit better with their theological sensibilities.[8]

The Process of Textual Criticism

Up to this point, our focus has been on introducing the need for textual criticism, the sources for textual criticism, and the kinds of problems that show up in manuscripts. Without understanding those important concepts, it would be challenging to begin the process of textual criticism. Now that we have laid the foundation with the tools for textual criticism, let us now discuss how we can determine with confidence the text of the Scriptures from the manuscripts we have available to us. The process outlined below is meant to be a helpful guide for the layperson who is just getting started, although this is no substitute for guided study in a seminary curriculum.

Step 1: Read Several English Translations from Differing Viewpoints

Many of our readers’ primary language is English, rather than Hebrew, so we will begin with an accessible suggestion for our English readers. For the vast majority of text, the Jewish Bible is agreed upon and translated into English similarly by varying religious groups. Although each translation has a different translation philosophy behind it (more literal versus more thought-for-thought), the essential meaning of the translations almost always agrees. If an Orthodox Jewish translation of a verse agrees with a more liberal Jewish translation, and agrees with an evangelical Christian translation, and a Catholic translation, then there is good reason to believe that there are no significant textual problems with the verse. As a starting point, we suggest consulting these translations:

| The Stone Edition (ArtScroll) | Orthodox Jewish, thought-for-thought translation |

| 1917 JPS Translation | American Jewish, literal translation based on King James Version |

| 1985 JPS Translation | American Jewish, thought-for-thought translation |

| The New American Standard Bible, 1995 Edition | Protestant Evangelical, literal translation |

| The English Standard Bible | Protestant Evangelical, literal translation |

As a rule, a more literal translation is better for textual criticism, since it attempts to stay closer to the meaning of the original language. The Masoretic Text is the base language (vorlage) of each of the translations above.

Step 2: Note Significant Differences and Predict Whether a Textual Problem May be the Cause

Not all differences between English translations are due to textual problems. In fact, very few of them are. Most translation differences are due to the translators’ philosophy (literal versus thought-for-thought). For example, the Scriptures include figures of speech that were common in ancient Israel, but sound odd to readers today. For example, it is common for the Scriptures to describe God as “long of nostrils” (אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם, see Ex. 34:6; Num. 14:18; Joel 2:13). This is how the Scriptures often describe God’s slowness to anger, with the idiomatic idea that it takes a long time for God’s “nostrils” to flare. A literal translation would retain “long of nostrils,” but even the most literal English translations avoid this. A contemporary rendering—something that makes sense to contemporary English readers—would be to translate as “slow to anger,” which most do.

With practice, a reader of multiple English translations can be “tipped off” to a problem in the Hebrew text. Checking the footnotes of the translations often helps. Sometimes a translation will place a footnote next to a phrase and say, “Meaning of Hebrew uncertain,” or, “LXX says ____.” These footnotes may be clues that explain why the translations disagree with each other on a certain word or phrase.

Once you have a hunch that there is a textual problem with a certain verse, it is time to leave the English translations behind. Original text language skills (Hebrew, Greek, etc.) will be necessary from this point on.

Step 3: Consult Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS)

Open up a copy of the BHS to the passage in question (this is paid only; get it in Logos or in print). Look in the text for a lowercase English letter in superscript after the “problem word” or phrase. If there is no superscript, then that means there are no significant textual issues with that word or phrase, so your hunch about a textual problem was probably wrong. However, if there is a letter, look at the bottom of the page (or click on the superscripted letter in digital format) for the associated note in the textual apparatus. These notes will give a summary of the relevant textual variants for the word or phrase. Understanding the abbreviated notation of the BHS is a challenge, so we recommend the book Understanding BHS by Wonneberger.[9]

Step 4: Consult the Primary Sources from the Apparatus

Even though the BHS apparatus usually includes the original language text of the textual variants, it is good scholarly practice to lay one’s eyes on the primary sources themselves. If the BHS apparatus mentions readings from the Septuagint, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Aquila, then track down each of these sources and read them for yourself.

Step 5: Create a Table of Witnesses

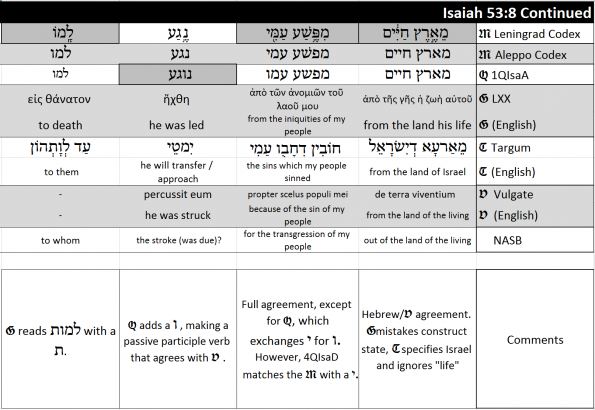

With all your textual witnesses open in front of you, write down each of the variants in a table. For example, this table of witnesses was created for Isaiah 53:8 in Microsoft Excel:

Putting the textual data in table format helps us organize and see the variants much easier. Translate each witness into English to clearly bring out the meaning. Note that this table goes from right-to-left, following the Leningrad Codex at the top as the most important textual witness.

Step 6: Summarize the Differences between the Versions

Now that the raw textual data is open before you in one easy-to-consult table, the real fun begins. Put on your detective cap and figure out what went wrong. Look for changes in letters. Look for omissions and additions and the other classes of problems listed above. Translate the non-Hebrew sources back into Hebrew (the vorlage) and compare the vorlage with the Masoretic and Dead Sea Scrolls. Make a new “Comments” row at the bottom of your table to summarize your findings. In our portion of Isaiah 53:8, there are significant textual variants in each column, and we have summarized the variants in the comments row:

In the first column of text (at right), there are problems with the Septuagint and the Targum, but the Hebrew is consistent, and the Vulgate agrees with the Hebrew. In the second column, there is a yud-vav interchange that leads to a different meaning of a word. In the third column (נגע), the Dead Sea Scrolls has an extra vav, leading to a passive verb that agrees with the Vulgate. Finally, in the last column, the Hebrew is intact, but the Septuagint seems to have seen a taf at the end of its Hebrew vorlage, leading to a translation of “to death.”

Step 7: Play Detective and Solve the Case

Now that the evidence is laid out, and the differences between the texts are highlighted, we now ask ourselves, “How did these variations happen?” Instead of being a detective investigating a murder case, we are detectives playing whodunit with a textual mystery. The best way to begin is to ask questions and look for leads.

Were all the sources looking at the same Hebrew word, or was there a second or third version of the word available to the sources? Do the sources disagree in the verb meaning, but agree in the verb grammar?[10] Was there a scribal error? Was there a vocalization difference? What could explain an omission, addition, misspelling, or one of the other classes of textual problems discussed above? What hypothesis best fits the relevant data?

Coming to conclusions on these matters requires many different steps of reasoning that will be decided differently by different scholars. For example, if one believes that the Masoretic Text is without error, then one will likely justify the MT’s choices above other sources. Other scholars prefer the reputation of the Septuagint, and therefore prefer its readings, and others want to defer to the Dead Sea Scrolls as the most ancient Hebrew version.

The human factor of what scholars want to be true is always a threat to textual criticism. But we should not let the science of textual criticism be dependent upon preconceived notions. We should be willing to come up with the most plausible and probable hypothesis, even when it is uncomfortable to us.

Here are some principles that should guide our reasoning:

Although textual criticism is a science, it is also an art. Mastery of the art will only come with practice and through the example of other textual critics. We hope that these introductory articles have increased your knowledge about textual criticism and given you an appetite to learn how to do it yourself. We end this article with a fitting conclusion about the aims of this holy art. Widder writes,

When we consider that the Bible was transmitted by hand and in harsh climates for thousands of years, we can only marvel that such a small percentage of the text shows notable variation (10 percent of ot and 7 percent of nt). Most of these variants are insignificant copying errors, and the others are largely unrelated to significant doctrinal issues.

Ultimately, we can have confidence that the Bible we use reflects a high degree of accuracy. The variants in biblical manuscripts are not challenges to the authority of God’s word. Rather, they reflect God’s use of human instruments in the divine process of authoring and preserving His sacred text. Through the efforts of textual critics, He continues to employ human agents in preserving His Word.[11]

Bibliography

Anderson, Amy, and Wendy Widder. Textual Criticism of the Bible. Edited by Douglas Mangum. Revised Edition. Vol. 1. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018.

Carasik, Michael, ed. Genesis: Introduction and Commentary. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2018.

Metzger, Bruce M. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Singer, Isidore, ed. The Jewish Encyclopedia. 12 vols. New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1901–1906.

Tov, Emanuel. “Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, Methodology.” In The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Magnum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Wegner, Paul D. A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods & Results. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006.

Wonneberger, Reinhard. Understanding BHS: A Manual for the Users of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 2nd rev. ed. Vol. 8. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 1990.

Footnotes

- For this section, we are indebted to the works of biblical scholars Paul Wegner, Amy Anderson, and Wendy Widder, which are listed in the bibliography. They provided the major categories of mistakes and also provided many of the textual examples listed in this article. ↑

- Emanuel Tov, “Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, Methodology,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. John D. Barry et al. (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016). ↑

- Amy Anderson and Wendy Widder, Textual Criticism of the Bible, ed. Douglas Mangum, Revised Edition, vol. 1 (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018), 25–26. ↑

- Isidore Singer, ed., The Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1901–1906), s.v. Azazel. ↑

- Verse 3 in Christian Bibles. Only the numbering is different. ↑

- Emphasis added. Paul D. Wegner, A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible: Its History, Methods & Results (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 54. Wegner quotes from Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 3rd ed. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1992), 195. ↑

- Wegner, Student’s Guide, 53. ↑

- Rashi’s comment on the verse: “Abraham had not gone to stand before Him; rather, it was the Holy One who had come to Abraham to say what He said in vv. 20–21. So our phrase really should be, ‘while the Lord remained standing before Abraham.’ The text as it stands is a ‘correction of the scribes,’ that is, it was reversed by the Sages.” Michael Carasik, ed., Genesis: Introduction and Commentary (Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2018), 162. ↑

- Reinhard Wonneberger, Understanding BHS: A Manual for the Users of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, 2nd rev. ed., vol. 8 (Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 1990). ↑

- I.e., one source that says, “he was struck” and another source that says, “he was led,” which disagree in their base verb but agree in being a third person masculine passive verb. This is the case in column 3 of the spreadsheet above, under “נגע” ↑

- Wendy Widder, Textual Criticism, ed. Douglas Mangum, Lexham Methods Series (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2013), 159–160. ↑

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.