Figure 1 – Codex Zacynthius, a Greek New Testament, dating to roughly 1200 CE, University of Cambridge

Why Read the New Testament?

“I’m Jewish.” That is a common response that many Jewish people give when asked questions about Jesus and the New Testament. Under the surface, the implied claim is that Jesus and the New Testament are not topics to bring up in polite Jewish company. The New Testament is for the Gentiles, but Jewish people have the Hebrew Scriptures.

And yet, despite the claim that the New Testament is not for Jewish people to read, there remains an uncanny attraction and curiosity in the Jewish community to break that taboo. There is something alluring about the mere existence of books that one is not supposed to read, and the books of the New Testament are not just any forbidden books—they are books written by Jews, about a Jew, taking place in Judea, and beloved by billions of people around the globe. The New Testament bears witness to ancient Jewish customs, halakhic disputes, diasporic communities, and much more. Without the pages of the New Testament, many historical details about ancient Jewish people would have been lost forever. Even its name is derived from the Hebrew: Brit Hadashah (בְּרִית חֲדָשָׁה, Jer. 31:31). Of course there is something fascinating about the New Testament!

However, some readers have been exposed to skeptics and opponents of the New Testament’s message, leading to doubts about its historical trustworthiness. These readers do not choose to leave the New Testament closed; instead, they open it up to devise theories and arguments for why the New Testament ought to be dismissed. If this describes you, then you have come to the right place.

The primary purpose of this article is to investigate the historical, textual, and literary backgrounds of the New Testament. Along the way, we will deal with some common misconceptions about its authors and its historical reliability. Further articles on the site will address questions of lost Gospels, alleged Gospel contradictions, and charges that the New Testament is antisemitic.

What is the New Testament?

The New Testament is a series of biographies[1] and letters[2] written by first-century Jewish authors[3] for the purpose of explaining the implications of the life, death, and resurrection of Yeshua, a rabbi from Judea. The authors of the biographies and letters either knew Yeshua personally or were closely associated with those who did.[4] Yeshua’s followers considered the biographies and letters to be just as inspired by God as the Tanakh was.[5] The New Testament was written by multiple authors in various locales (Judea, Rome, Asia Minor), utilizing various literary genres (biography, theological treatise, personal letter, apocalypse).

The twenty-seven “books” of the New Testament circulated independently around the Roman Empire for generations but began to be assembled into collections in the second century CE.[6] These collections became so accepted that even second-century groups outside the mainstream Jesus-following movement still defined the New Testament largely as we do today.[7] From these books, we get a window into the life of Jesus, his early followers, and the history and theology of their movement. The books were originally written in Greek, but have been translated into a multitude of world languages, starting as early as the second century CE. Their message has been taken to the ends of the earth, far beyond the Judean locale where many of the books’ events took place.

Below are the twenty-seven books included in the New Testament:

|

The New Testament |

|

| The Gospels: Biographies about Yeshua

1.Matthew (Mattiyahu)

2.Mark

3.Luke

4.John (Yohanan)

The History of the Early Jewish-Gentile Congregations 5.Acts of the Apostles

The Letters of Paul (Sha’ul) 6.Romans

7.First Corinthians

8.Second Corinthians

9.Galatians

10.Ephesians

11.Philippians

12.Colossians

13.First Thessalonians

14.Second Thessalonians

|

The Letters of Paul (Continued)

1.First Timothy

2.Second Timothy

3.Titus

4.Philemon

An Anonymous Sermon to Messianic Jews 5.Hebrews

Letters by Other Apostles 6.James (Ya’acov)

7.First Peter

8.Second Peter

9.First John

10.Second John

11.Third John

12.Jude

The Apocalyptic Conclusion 13.Revelation / The Apocalypse

|

This section has described the New Testament as it has been accepted by Jesus’ followers since the second and third centuries CE. For the remainder of this article, we will discuss how the New Testament has gotten into our hands and how we can determine who wrote it and when. The authorship and the dating of the New Testament books are critical if they are to be deemed trustworthy sources of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

Who Wrote the New Testament?

If we are investigating the veracity of the New Testament, then we must consider the authorship of its books. Quite simply, if the books of the New Testament were not written by followers of Yeshua or by those closely associated with them, then the New Testament is less historically reliable. On the other hand, if those closely associated with Yeshua did write the books, it increases the likelihood that the New Testament books were firsthand accounts of his life, teachings, death, and resurrection.

In this article, we will be discussing two types of evidence by which we may consider the authorship and the dating of ancient works: internal and external evidence. Internal evidence refers to the evidence found within the text. This includes the claims made in the text, linguistic style, geographical descriptions, literary conventions, quotations of other works, and other details contained within the words of the text. External evidence refers to the evidence existing outside the text, such as manuscript evidence, quotations of the work in other sources, and commentaries upon the work from other sources. To begin, we will examine examples of internal evidence to consider regarding the authors of the New Testament’s books.

Internal Evidence for Authorship

Some books in the New Testament actually include the names of the authors in their text. Although the use of an author’s name is not conclusive evidence, it does narrow the field and identify a leading candidate for the book’s authorship. New Testament books that explicitly include the author’s names are:

These works are letters, and thus they contain traditional greetings from the author (including his name) at the beginning of the letter. Other genres of literature, such as historical narratives (Gospels, Acts) and sermons (Hebrews) did not have established literary conventions for including an author’s name, so this is a likely reason why no names are included in some other New Testament books.

Some of the books in the New Testament do not include their authors’ names, but they contain uniquely similar content, syntax, and vocabulary as other books. These telltale signs indicate that the anonymous author composed multiple books in the New Testament. If an author can be identified for one of the books, then it is most likely that the same author is responsible for the others:

The authorship of other anonymous works may be determined to a certain degree based on the biographical details included in the texts. For example,

In sum, although we do not have explicit claims of authorship contained in every one of the books of the New Testament, there are many biographical and historical details included in the texts by which we may make an educated guess as to the author of these works. However, we are not limited to these internal features of the New Testament when we make these determinations; assistance may be found outside the text as well.

External Evidence for Authorship

Everything discussed above relates to internal evidence for New Testament authorship. Now we will shift our focus to the external evidence that may be found outside the text.

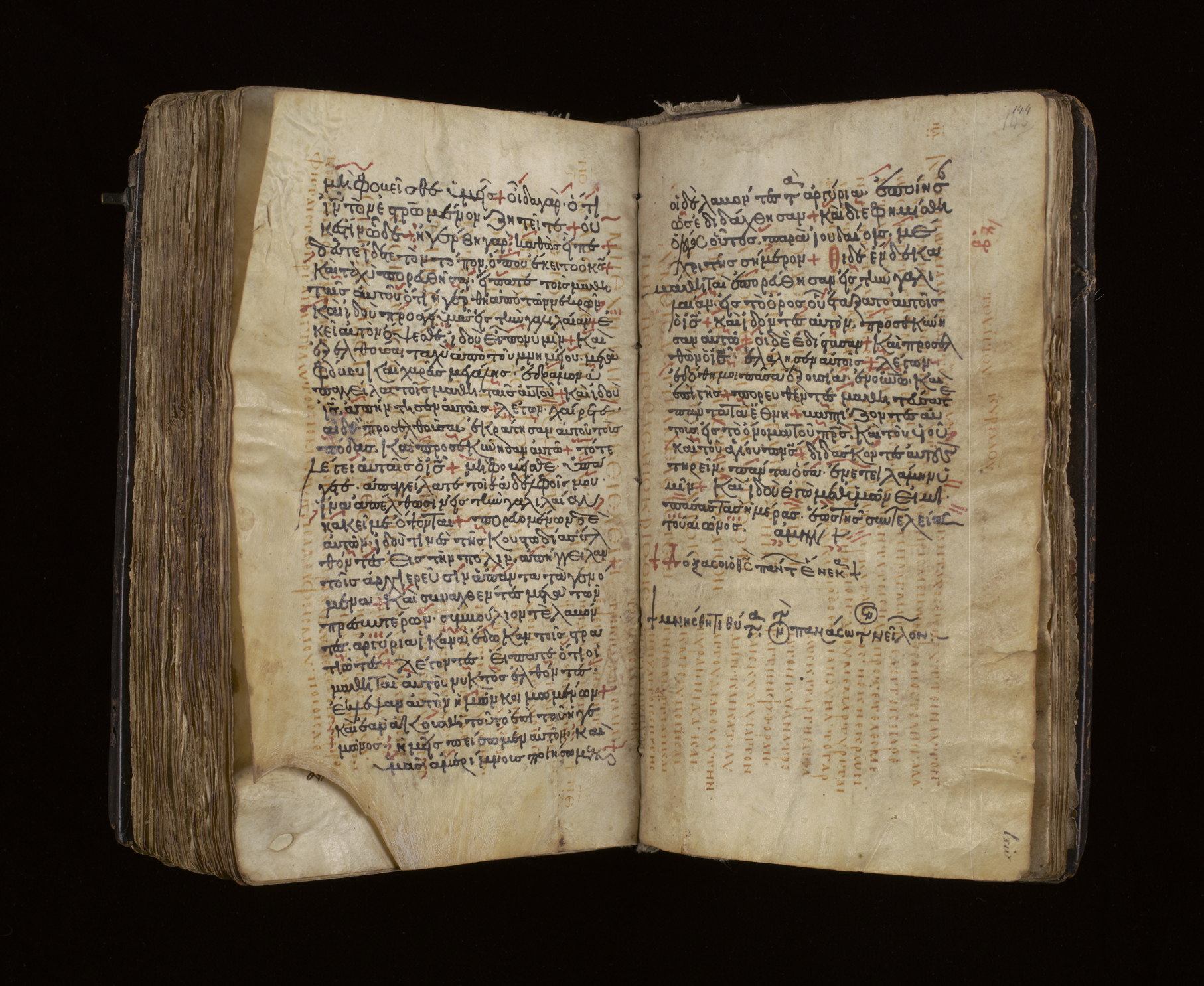

The first type of external evidence to examine is the ancient manuscript evidence of the New Testament. The scribes who copied the manuscripts often added titles to the books they were copying. For example, below is a scan of the third-century manuscript P75, which shows the end of the Gospel of Luke and the beginning of the Gospel of John, written in Greek:

In this portion of the manuscript, there is a gap in the middle of two blocks of text. Above and below the gap, there are scribal additions. The scan could be laid out like this, with the Greek translated:

[Greek text from the Gospel of Luke, chapter 24]

The Gospel According to Luke

[Gap]

The Gospel According to John

[Greek text from the Gospel of John, Chapter 1]

We see here that the scribe has added titles to these two Gospels, and these titles are claims of authorship. Whereas the Gospel of Luke does not name its author within its text and the Gospel of John leaves us speculating which disciple of Yeshua wrote the Gospel, the scribes identified the authors for us with these titles.

While this does not provide absolute proof of authorship (because the scribes themselves could have been in error), it is important to note that these early manuscripts never disagree about the Gospels’ authorship. They consistently label them as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. These titles attest to a very early tradition of authorship attributed to the Gospels. What we know as Matthew today was never called Mark, and what we know as Luke today was never called Peter or Thomas. If misattribution occurred, it must have occurred very early, so early that there is no evidence remaining. But the earlier one goes beyond a manuscript’s dating (in the case of P75, the third century), the more likely the claim of authorship is to be authentic because we enter into the first-century timespan of Yeshua’s original followers.

Another type of external evidence is the scribal addition of a prologue added before the biblical text. Some of the most famous ancient prologues are called the Marcionite Prologues[8] and the Anti-Marcionite Prologues.[9] These date to the second century and identify the authors of the Gospels and the Pauline letters. For example, a prologue to Mark says with a dash of humor,

Mark recorded, who was called “stumpy finger,” because he had fingers that were too small for the height of the rest of his body. He himself was the interpreter of Peter. After the death of Peter himself, the same man wrote this gospel in the parts of Italy.[10]

Of Luke, it is said,

Indeed Luke was an Antiochene Syrian, a doctor by profession, a disciple of the apostles: later however he followed Paul until his martyrdom, serving the Lord blamelessly. He never had a wife, he never fathered children, and died at the age of eighty-four, full of the Holy Spirit, in Boetia…. And so at once at the start he took up the extremely necessary [story] from the birth of John, who is the beginning of the gospel… And indeed afterwards the same Luke wrote the Acts of the Apostles.[11]

Authorship claims were also made in the Muratorian Fragment (roughly 170–80 CE), a list of canonical New Testament books that were in use at the time.[12] All the books of the current New Testament were included in the fragment except for Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, and 3 John. For the books that were included, the names and backgrounds of the authors were described. F.F. Bruce produced a translation of the fragment, given here in part:

The third book[13] of the gospel: according to Luke. After the ascension of Christ, Luke the physician, whom Paul had taken along with him as a legal expert, wrote [the record] down in his own name in accordance with [Paul’s] opinion. He himself, however, never saw the Lord in the flesh and therefore, as far as he could follow [the course of events], began to tell it from the nativity of John.

The fourth gospel is by John, one of the disciples….

The Acts of all the apostles have been written in one book. Addressing the most excellent Theophilus, Luke includes one by one the things which were done in his own presence, as he shows plainly by omitting the passion of Peter and also Paul’s departure when he was setting out from the City for Spain….[14]

Finally, there is an additional class of external evidence included in Gentile Christian writers’ early accounts about the dates and authorship of the books of the New Testament. These include the writings of Papias, Clement, Ignatius, Justin, Tertullian, Irenaeus, and many more. For example, Justin Martyr, circa 150 CE, ascribed Revelation to Yeshua’s apostle John[15] and argued that Yeshua’s apostles composed the Gospels.[16] These sources contain an entire patchwork of citations and discussions about the New Testament authorship, and they tend to agree about each of the New Testament books except for the books of Hebrews and 2 Peter.

In conclusion, the identities of the New Testament authors were commonly agreed upon beginning in the first century CE. There is a remarkable consistency to each of the claims of authorship, and the external evidence meshes well with the internal evidence provided by the books themselves. However, there are still unanswered questions about the authors and their identities, so investigation into their writings’ historical dating will be our next step.

When Was the New Testament Written?

In the game of “Telephone,” one person shares a message secretly with another person, who then shares what he or she heard to the next person, and this linear process of listening and repeating goes until the last person repeats to the whole group what was heard. The final report rarely ever carries the same meaning as the original message. The game’s appeal is to demonstrate how human communication often results in miscommunication and can lead to hilarious and nonsensical results. Communication is messy.

Historians have developed tools for addressing the kinds of problems created in a Telephone scenario. It is commonly accepted that a book written during the era of the events discussed therein is generally preferred over a book describing those events from centuries later without early eyewitness reports. Modern historiography reflects this principle: prioritize primary sources over secondary or tertiary ones. Highlight eyewitness reports over hearsay. In the game of Telephone, this would be like cutting out the middlemen and hearing the original message directly from the first person in the chain. However, even this move is not enough for full trustworthiness, for the first person could have begun the Telephone chain with a lie.

Some people come to the New Testament with the game of Telephone in mind. Some think that the New Testament is a late production of the final stage of textual transmission that is far removed from the original events of Jesus’ life. How can anyone be sure that the final message on the page was accurately transmitted to the twenty-first century from the original authors? Haven’t there been mistakes and corruptions made along the way? Likewise, is the New Testament reflective of primary sources, or the result of hearsay or forgery? Were the authors of the New Testament eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus and his early followers? Moreover, even if they were eyewitnesses, how can we be sure that their reporting was accurate (not false)? These are important questions, and they revolve around three topics:

For the remainder of this article, we will give evidence and commentary concerning the first two topics. It is our position that (1) the New Testament was written by eyewitnesses or close associates of eyewitnesses, (2) the integrity of the New Testament text available today is nearly identical to the original manuscripts, and that the evidence in favor of these two points increases the plausibility that (3) the New Testament reports are true.

One way of answering these questions—or at least increasing the plausibility of one’s answer—is to investigate the date of composition of each of the books of the New Testament. In general, early dates leave less time for corruption and make eyewitness claims more plausible. Late dates make eyewitness claims less plausible and also provide more time for textual corruption. Early dating is an important factor in this discussion because a book written during the lifetime of eyewitnesses to Jesus’ life could be corrected or denounced by the eyewitnesses themselves. This would be like the first person in the Telephone game correcting each person’s whisper to the next person in the chain.

Unfortunately, because the historical record cannot be known with mathematical certainty, personal bias can play a strong role in one’s dating of the New Testament works. Skeptics often propose theories of New Testament origins that conform to late dates, whereas followers of Jesus often propose theories dating to the lifetime of eyewitnesses. Historical reconstructions of New Testament origins can provide great hinderances or powerful reasons for belief in Jesus as the Messiah.

When discussing this topic, Asher Norman, a Jewish lawyer opposed to Jews believing in Yeshua, portrayed the Gospels as second-century CE documents that could not have been written by Jesus’ original followers.[17] Likewise, the organization Jews for Judaism places the origin of some of the New Testament writings in the second century.[18] If these determinations are correct, then it is more likely that the New Testament books were forgeries, fictions, or redactions,[19] rather than the authentic recollections of eyewitnesses. New Testament scholar Paul Barnett comments,

Many scholars appear to think the field for their studies of the New Testament is temporally undefined, boundary-less, somehow able to accommodate the most remarkable explanatory hypotheses. The same holds true for various rhetorical and literary theories that have arisen to explain the character of the texts. It is as if the documents of the New Testament evolved over many centuries rather than within just a few decades.[20]

One’s bias also plays a role when it comes to a major world event that influences one’s position on the dating of the New Testament: the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE. In multiple places in the Gospels, Yeshua is recorded as prophesying the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple around 30 CE.[21] If the phenomenon of prophecy exists, and Yeshua prophesied the destruction forty years before it happened, then this would be powerful evidence for his identity as the Messiah. Less likely is the supposition that his prophecy was merely a lucky guess. However, if the phenomenon of prophecy does not exist, or if one has already predetermined that Yeshua cannot be the Messiah, then one may be motivated to deny that Yeshua ever made such a prophecy. In line with this, many claim that post-70 redactors placed Yeshua’ prophecy on his lips in the Gospels to make it look like he was a prophet. A late date to the New Testament necessarily follows.

These are significant questions to discuss about the origins of the New Testament. Are the questions of the New Testament’s dating and authorship hopelessly mired in subjective and biased historical reconstructions? No, we do not believe so. There is a significant amount of evidence to be considered when discussing the origins of the New Testament documents. As with our discussion on authorship, we will begin our investigation into the dating of the New Testament by looking at the internal and external evidence pertaining to its origin.

Internal Evidence for Dating: Details Contained Within the New Testament Text

Internal evidence for the dating of the New Testament refers to details included in the text which indicate a quantifiable range of dates for the text’s original composition. In this section, we will consider chronological, geographical, linguistic, and other internal factors that constrain the dating of the New Testament to dates within the first century CE.

It was once in vogue for scholars to apply evolutionary principles to New Testament thought, supposing that the New Testament was the product of several generations of mutations that corrupted what the historical Jesus taught. The general idea was that Jesus was a typical Jewish man who preached a Jewish message, but his later followers embellished accounts from his life and turned him into something akin to a Greek demigod. This process, no doubt, could not have been done quickly, lest the original hearers of Jesus correct the emerging narrative. Thus, over the course of a century or two, after the first generation of Jesus’ followers died off, new innovations and legends about the Jesus-story emerged and became a new orthodoxy. The New Testament as we have it is the product of this legendary accretion, which cannot be assigned a first-century date or anything approaching an accurate historical record.

The theory just summarized has become a relic of twentieth-century scholarship that has been heavily discussed and finally dismissed. Several lines of investigation have challenged the late-date evolutionary thesis, including the presence of binitarianism in Second Temple Judaism,[22] the evidence of early Yeshua-belief contained within Paul’s letters, and linguistic evidence that the New Testament was written by authors with an authentic Jewish (not Greek) pedigree.

Internal Evidence #1: The Creed in 1 Corinthians 15:3–8 Dated to the Mid-30s

This section will investigate an important passage in one of Paul’s letters that indicates that the key teachings of the New Testament that we have today were actively being taught by Jesus’ eyewitness followers in the 30s CE. This undercuts many skeptical theories of the New Testament’s legendary origins.

In 1 Corinthians 15:3–8, Paul wrote a series of statements that he claimed to have received from others. It is generally agreed upon by scholars that Paul wrote 1 Corinthians sometime between 53–55 CE based on the chronology in Acts 18 and a dated Roman inscription.[23] Since Yeshua was likely crucified in 30 or 32 CE, Paul’s letter is dated within 25 years of Yeshua’s death.

The late Orthodox Jewish scholar Pinchas Lapide gave multiple reasons why he believed this passage was early and authentic: its Semitic terminology, its non-Pauline structure, its double reference to “the Scriptures,” the passive form of the verbs to hide the divine name, and the reference to the Aramaic name Cephas.[24] On the basis of factors such as these, scholars have identified this as a creed that Paul did not create himself, but rather one that he inherited and passed along.

The creed is as follows:

For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received:

that [Messiah] died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures,

that he was buried,

that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures,

and that he appeared to Cephas,

then to the twelve.

Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time,

most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep.

Then he appeared to James,

then to all the apostles.

Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me (1 Corinthians 15:3–8).

In a rabbinic mode of speaking, Paul said, “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received.” The verbs “delivered” and “received” are common words used in Judaism to refer to oral traditions with an authoritative status. For example, m. Pirke Avot 1:1 reads, “Moses received (קבל) Torah at Sinai and handed it on (ומסרה) to Joshua.”[25] In the same way, Paul said that he received a creed and then passed it on to his audience, the Corinthians. The verb “delivered” is in the past tense (aorist), indicating that Paul had already delivered the creed to the Corinthians at a previous date, which most scholars place during Paul’s visit to Corinth in 50–51 CE.

Thus, the creed that Paul received was delivered to the Corinthians between 18–21 years after Yeshua’s crucifixion. We are whittling away the time gap for this passage, but we can go even further back. Paul stated that he received this creed himself at some time in the past, and that it was of “first importance.” The question to ask is, “When, and through whom, did Paul receive this important message?” New Testament scholar Michael Licona writes,

When did Paul receive the tradition? A few possibilities readily present themselves. We may first consider the location of Damascus just after Paul’s conversion [Acts 9], which is generally placed one to three years after the crucifixion of Jesus. According to Luke, Paul entered Damascus after his conversion experience. After Ananias healed his resulting blindness three days later, he spent several days with the Damascus Christians and increasingly became more powerful in his ability to confound his newly found Jewish opponents, proving that Jesus is Messiah (Acts 9:19–22). Perhaps he learned tradition during this period from Ananias or some of the other Christians there. If this is where Paul learned portions of the tradition, its reception by Paul may be dated to within three years of Jesus’ death.[26]

Another possible date when Paul could have learned this was when Paul spent fifteen days with the Apostle Peter in Jerusalem three years after coming to believe in Jesus (Gal. 1:18). This would also place the giving of the creed to Paul in the region of 3–5 years after the crucifixion. Licona gives an extensive summary of scholars’ opinions on the dating of this creed, with nearly all agreeing that it dates from within a few months of Jesus’ crucifixion, to within five years after it.[27]

In the creed, it is claimed that Yeshua rose from the dead, that there were multiple witnesses of his resurrection, that these events took place according to the prophecies in the Scriptures, that Yeshua’s death occurred “for our sins,” and that a group of Yeshua’s followers, called the apostles, were living eyewitnesses of the truth of the claims. The early creed in 1 Corinthians 15 summarizes the message of the New Testament, and it is dated as early as 30–35 CE.

This is the embryonic Gospel message—the Good News. It did not develop over decades or a century of time. It did not develop divorced from the time period of living eyewitnesses. It did not develop in far-off Gentile locations, but likely in Jerusalem, where Aramaic was spoken and two of the named men (Cephas and James) lived.

Consequently, any theory about the origin of the New Testament must account for these early beliefs and this early creed. It is no longer sufficient to cast doubt upon the authorship and dating of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. It is no longer credible to postulate second-century conspiracy theories about the origins of specific doctrines. Even if, for sake of argument, Matthew, Mark, and Luke were written in the second century, not by eyewitnesses, one’s theory still has to account for why a group of Judean Jews started believing by 35 CE in a risen Messiah who died for their sins according to the prophecies in the Hebrew Scriptures. One also must account for the many other features of the Yeshua-following movement that can be dated to within twenty years of Yeshua’s crucifixion, such as the growth of the Jerusalem and Antioch congregations, the repentance and transformation of Paul, and the presence of Jewish followers of Jesus in Rome.[28] As Paul Barnett quips,

The imaginative historian, like a flighty poodle on a retractable lead, must be reeled in by that mundane and boring reality called evidence, evidence weighed according to criteria and “rules.” Otherwise history writing is fiction writing.[29]

Internal Evidence #2: Geographical and Historical Details About Pre-70 CE Jerusalem

The New Testament includes geographical and historical details about Jerusalem that confine the dates of composition to a very narrow range, often implying a date of composition before 70 CE.

For example, two of the most important dates for the dating of the New Testament are 70 CE, the date of the Roman destruction of the Temple, and 135 CE, the year Rome suppressed Bar Kochba’s rebellion and banned Jewish people from entering Jerusalem. If an ancient work describes Jerusalem’s specific geographical and architectural features from a first-person Jewish perspective, to be authentic as an eyewitness report, the account had to be written by a Jewish person who experienced Jerusalem before 135 CE.[30] After that date, no Jewish author could authentically describe Jerusalem using a first-person perspective if he had not experienced Jerusalem by 135 CE, since Jews could not enter Jerusalem after that date.

Likewise, if the features of Jerusalem are described from a third-person perspective, to be an authentic report, the account had to be derived from Jewish people who experienced Jerusalem before 135 CE.[31] In other words, ancient Jewish reports about Jerusalem are only plausible if they are dependent upon eyewitness reports—either from what the author himself experienced before 135 CE, or from the author’s access to eyewitness reports from before 135 CE. In this example, the year 135 CE is functioning as a limiting date, which historians call a terminus ad quem.

The year 70 CE also functions as a terminus ad quem for descriptions of Jerusalem relating to features that were destroyed by Rome in that year. If a work discusses details about Jerusalem and the Temple that were only present before the destruction of 70 CE, then to be authentic reporting, the account had to be (1) written by or (2) derived from an eyewitness of Jerusalem as it existed before 70 CE.

These dates and the historical reasoning concerning them are very important for determining whether the New Testament contains eyewitness reports. The New Testament contains many historical details about Jerusalem and the Temple, corroborating its claims to eyewitness authorship. Many of these details may be confirmed with the Jewish historian Josephus’ eyewitness reporting, who knew Jerusalem intimately before its destruction in 70 CE. For example,

The most likely explanation for the existence of these historical and geographical details in Luke, John, and Acts is the reason given by the documents themselves: they were written by eyewitnesses (John) or by those who had consulted eyewitnesses (Luke and Acts). It is not unreasonable to extend this logic to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, which include pre-70 CE details as well. If so, then the books of the New Testament with these details are to be dated within living memory of pre-70 CE Jerusalem.

Internal Evidence #3: Semitisms in the New Testament that Likely Date from Pre-70 CE

As with geographical and historical details, a similar argument for the pre-70 CE dating may be made through a linguistic analysis of the New Testament literature. Scholars point to the presence of “Semitisms” in a New Testament work as a sign of early dating.[34] Semitisms are Aramaic and Hebrew phrases and terms, written in Greek characters, most commonly used by someone living in a Jewish community.[35] We know from outside sources that the majority of Yeshua’s followers in the second century were from Gentile origins, so the presence of Semitisms in the New Testament would argue for a date when most believers in Yeshua lived within a Jewish community.

The Aramaic phrase marana-tha (מָרַנָא תָא, “O Lord, Come!”) and the ubiquitous amen (אָמֵן, “may it be true”) are two examples of Semitisms in the New Testament (1 Cor. 16:22, Rom. 11:36, John 3:3). Below is a list of many more:

Table 2 – Semitisms in the New Testament[36]

| ἀμήν (אָמֵן, amen, truly)—129 uses in the NT

πάσχα (פַּסְחָא, Passover)—29 uses ῥαββί (רַבִּי, rabbi)—15 uses ὡσαννά (הוֹשַׁע נָא, save please!)—6 uses ἁλληλουϊά (הַלְלוּ־יָהּ, Praise Hashem!)—4 uses μάννα (מָן, manna)—4 uses ἀββά (אַבָּא, abba, father)—3 uses μαμωνᾶς (מָמוֹנָא, mammon)—3 uses |

ἐλωΐ (אֱלָהִי, my God)—2 uses

ἠλί (אֵלִי, my God)—2 uses λεμά (לְמָא, why)—2 uses ῥαββουνί (רַבּוּנִי, my master)—2 uses σαβαχθάνι (שְׁבַקְתַּנִי, you have forsaken me)—2 uses σαβαώθ (צְבָאוֹת, hosts)—2 uses ἐφφαθά (אֶתְפְּתַח, be opened)—once κορβᾶν (קָרְבָּן, a gift consecrated to God)—once |

The authors of the New Testament books did not translate these words into Greek, but rather transliterated them into Greek characters. Why are these Aramaic and Hebrew phrases included within a collection of books written in the Greek language? This is not unlike English speakers using words like schlep, chutzpah, kvetch, and shmutz in everyday language. English speakers who use those words have come into contact with, and perhaps even live within, Jewish communities who use those Yiddish words.

In similar fashion, the use of Semitisms in the New Testament is best explained if the books were authored by those who lived within a Jewish society. The authors of the New Testament used Semitisms because they themselves were Jews and spoke the languages of Israel. They had been to so many synagogue services with prayers ending with אָמֵן that they wrote the word out as ἀμήν (amen) in Greek.

The use of these Semitisms places a chronological date upon the composition of the New Testament. For political and religious reasons, the phenomenon of Messianic Jews living in community with other Hebrew and Aramaic speaking Jews became increasingly difficult after 70 CE, and especially after 135 CE.[37] Many Jewish believers in Yeshua were forced out of synagogues and towns and had to live an in-between existence between church and synagogue.[38] Although this “parting of the ways”[39] was a process that took place over many years in a non-uniform fashion,[40] Jewish interaction with Jesus-followers using Semitic languages became less and less common after 70 CE.[41] From the second century onward, very few Gentile church fathers had any knowledge of Hebrew, with Origen (third century) and Jerome (fifth century) as rare exceptions. Consequently, based on later Christian ignorance of Semitic languages, any books in the New Testament containing Semitisms were likely written by authors who lived in Jewish communities before 70 CE.

Internal Evidence #4: The Dating of Acts to the Mid-60s

The book of Acts provides a historical account of the early Jewish believers in Yeshua roughly between 30–62 CE, starting from Yeshua’s resurrection. Acts has two main characters that drive the narrative: Yeshua’s lead disciple, Peter (Acts 1–12), and the Pharisee Sha’ul, also known as Paul (Acts 13–28). From other writers we learn that the Roman Emperor Nero executed Peter and Paul for the crime of following Jesus sometime between 62–68 CE.[42] Roman historian A.N. Sherwin-White remarked, “For Acts the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming.… Any attempt to reject its basic historicity even in matters of detail must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted.”[43]

The 60s were a tumultuous decade for both Jewish believers in Jesus and for all Jews living in Judea. Emperor Nero, as mentioned, became intent around 62 CE on killing Jesus’ followers, and the Roman historian Tacitus described the grisly lengths to which Nero went in order to exterminate them (Annals 25.44). In 66 CE, Nero also initiated a Roman campaign to invade Judea, but he died in 68 CE before Jerusalem was captured. The Holy City was finally overtaken in 70 CE by Emperor Vespasian, who promptly demolished the Temple and ended its priesthood, murdering and exiling more than a million Jewish people.[44] Rome was no friend to Jewish people or followers of Yeshua from the mid-60s onward.

The book of Acts is highly interested in telling the stories of Peter, Paul, and the growth of Jesus’ followers in Jerusalem, the location where roughly half of the book takes place. However, for some reason, Acts never mentions Peter’s death, Paul’s death, the Roman campaign against Judea, or the destruction of Jerusalem. Instead, it ends with Paul alive yet detained in Rome (Acts 28:30). Moreover, Acts describes many interactions between believers in Yeshua and Roman officials, but there is an optimistic tone, rather than one borne out of the bitterness of Roman persecution.

Scholars note that the absence of the fates of Peter, Paul, and Jerusalem in Acts is highly unusual, given Acts’ interest in the people and places involved.[45] It would be similar to finding a book on the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. without any mention of his assassination, or a book on the history of New York without any mention of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the city. The assassination and the attacks were catastrophic events that were universally recognized by all who lived through those eras. In the same way, for Jews (and Jewish believers in Jesus) living through the 60s CE, Nero’s persecutions and the war in Judea were similarly catastrophic and universally known. Why did Acts not mention them?

We cannot know for sure, but the most natural answer is to suppose that the book of Acts was written before the events took place. The events were not reported, because they were still in the future. In the same way, a biography on Martin Luther King Jr. without his assassination was likely written before 1968, and a book about New York history without mention of 9-11 was likely written before 2001.

New Testament scholar Darrell Bock, a Jewish believer in Jesus, discusses the dating of Acts in his major commentary, noting how those who date the composition of Acts after the destruction of the Temple (post 70 CE) often base their decision on factors outside of Acts itself. Bock writes, “Those favoring a late date tend to base it on the fact that Acts follows Luke’s Gospel and then argue that Luke’s Gospel was written in a post-70 setting. This view depends more on how Luke’s Gospel is dated than on evidence from Acts.”[46]

The Jewish Annotated New Testament (2011 edition) follows this logic. In a short section on the dating of Acts, Gary Gilbert writes, “The Gospel of Luke probably alludes to the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple (cf. 19.41–44; 21.20–24), which places its composition after 70 CE. While a precise date is impossible to establish, Acts was most likely composed early in the second century CE.”[47] In other words, since Luke (Volume I) contains historical details about 70 CE, and therefore must be written after 70 CE, then Acts (Volume II) must be written after 70 CE as well, even in the second century.

This is an example where a scholar’s presupposition (bias) against Jesus, supernaturalism, or prophecy comes into view (Gilbert does not indicate which one is factoring into his opinion). The passages Gilbert cites in Luke are where Jesus is prophesying about the future. Gilbert has made a religious choice to believe that such prophecies cannot possibly be historical, since Jesus cannot prophesy, and thus they were put into Jesus’ mouth at a later date. This is dating New Testament works by preconceived skepticism, rather than addressing the evidence at face value. If Gilbert were to set aside his skepticism and follow the historical evidence, he might find that Jesus’ prophecy in Luke only increases the stature of Jesus’ Messianic claims.

What if the historical evidence contained in Acts indicates a mid-60s date of composition? Then everything gets turned around. If Acts was written in the mid-60s, then Luke was written before that. The Gospels of Luke and Matthew made use of the Gospel of Mark,[48] so the Gospel of Mark was written before Luke. If so, then the chronology of the Gospels takes shape:

4. Acts, written mid-60s

3. Luke, written before Acts (early 60s?)

2. Matthew, written before Acts (Late 50s?)

1. Mark, written before Matthew and Luke (50s or 40s?)

If this is a generally correct chronology, then the presence of Jesus making prophecies about the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE is not evidence of a late date, but evidence that Jesus was who the Gospels claimed he was.

External Evidence for the Dating of New Testament Books

Besides the evidence we glean from the contents of the New Testament itself, we can also find evidence outside the text. Here are three external sources that help us date the books of the New Testament.

External Evidence #1: The Manuscripts of the New Testament

As an ancient collection of writings, the authors of the New Testament originally wrote upon parchments or scrolls by hand. However, such documents were susceptible to deterioration: the papyrus could tear, the ink could fade, and it could be subject to fire and other calamities. Because of these threats to ancient documents, those with financial means would copy and recopy manuscripts in order to safeguard the survival of their message. However, due to the ravages of time, very few original copies of ancient works survive today—the Dead Sea Scrolls are one of the rare exceptions. Scholars call the original copy of any work an “autograph,” and unfortunately, we do not have any autographs of the New Testament’s books.

At first glance, this may appear to be a significant problem for the New Testament’s reliability and accuracy. How can we trust that the New Testament is free from tampering? Couldn’t there have been additions and omissions placed in the text that we have today? While these are pertinent concerns, they are less important than one might think in the New Testament’s case.

Scholars of antiquity have long recognized the need to develop methods for studying ancient texts despite the time gap between the autograph and the earliest manuscript evidence still available. This is the field of textual criticism. Principles of textual criticism are necessary for any literary work penned before the printing press (fifteenth century CE), including works in the Tanakh, the New Testament, and those taught in any university’s classics department.

The New Testament is—by far—the best-attested group of ancient documents in existence, with manuscript evidence that predates all other major works of antiquity for which we also lack autographs. For example, the Greek philosopher Plato, a thinker who has had an incalculable influence on subsequent thought, wrote his autographs in the 400’s BCE. However, Plato’s earliest surviving manuscript dates to 895 CE, roughly 1,300 years after Plato wrote.[49] In comparison, the time gap between original composition and surviving manuscripts in the New Testament’s case is miniscule.

Although the evidence presented below will show the Tanakh and the New Testament as the winners for manuscript reliability, until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947 and afterward, the Tanakh would not have fared so well. Before 1947, Jewish and Christian readers of the Hebrew Tanakh needed to trust the accuracy of the Masoretic Text based on faith and tradition, rather than based on manuscript evidence. The scrolls’ discovery cut the time gap significantly for the last written books of the Tanakh (Zechariah, Haggai, Malachi), from 1,300 years down to the region of a few centuries. Despite the Dead Sea Scrolls’ discovery, there is still a significant time gap for the Torah, a gap of roughly a millennium (1400 BCE – 250 BCE). One must continue to trust that the Torah contains the words of Moses on the basis of faith and tradition, more so than on the basis of manuscript evidence.

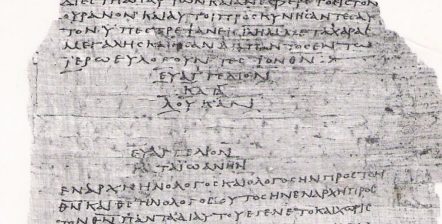

The New Testament does not suffer from the kinds of time gaps that are present with other works of antiquity. For example, below is the John Rylands Papyrus, also known as P52, the oldest manuscript currently known of the New Testament. It contains portions of the Gospel of John, and it dates to roughly 130 CE:

Most scholars believe that the Gospel of John was composed around 90 CE, meaning that this manuscript dates to within 40 years of the original autograph. This manuscript fragment is small and only contains a short portion of the Gospel of John, so it does not establish the integrity of the entire Gospel, let alone the integrity of the rest of the New Testament. However, it still provides a chronological datapoint that scholars must account for in their theories. Other early manuscripts of New Testament books include:

The earliest full copies of all the books of the New Testament are found in Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, both of which date to the fourth century CE, roughly a 150- to 250-year time gap from the original autographs.

How do these time gaps compare with other major works in antiquity? Below is a table[50] comparing the number of manuscripts we have available of the New Testament and Hebrew Bible versus the number we have for other ancient famous works:

| Author | Work | Date Written | Earliest MSS | Time Gap (years) |

| Homer | Iliad | 800 BCE | ca. 400 BCE | 400 |

| Herodotus | History | 480–425 BCE | 10th cent CE | 1,350 |

| Sophocles | Plays | 496–406 BCE | 3rd BCE | 150 |

| Plato | Tetralogies | 400 BCE | 895 | 1,300 |

| Caesar | Gallic Wars | 100–44 BCE | 9th CE | 950 |

| Livy | History of Rome | 59 BCE– 17 CE | Early 5th CE | 400 |

| Tacitus | Annals | 100 CE | 1st half: 850, 2nd: 1050 | 750 |

| Pliny, the Elder | Natural History | 49–79 CE | 5th CE | 400 |

| Thucydides | History | 460–400 BCE | 3rd BCE | 200 |

| Demosthenes | Speeches | 300 BCE | 9th-10th CE | 1,200 |

| Various | New Testament | 50–100 CE | 130 CE | 40–250[51] |

| Various | Hebrew Bible | 1400–400 BCE | 250 BCE | 150–1200[52] |

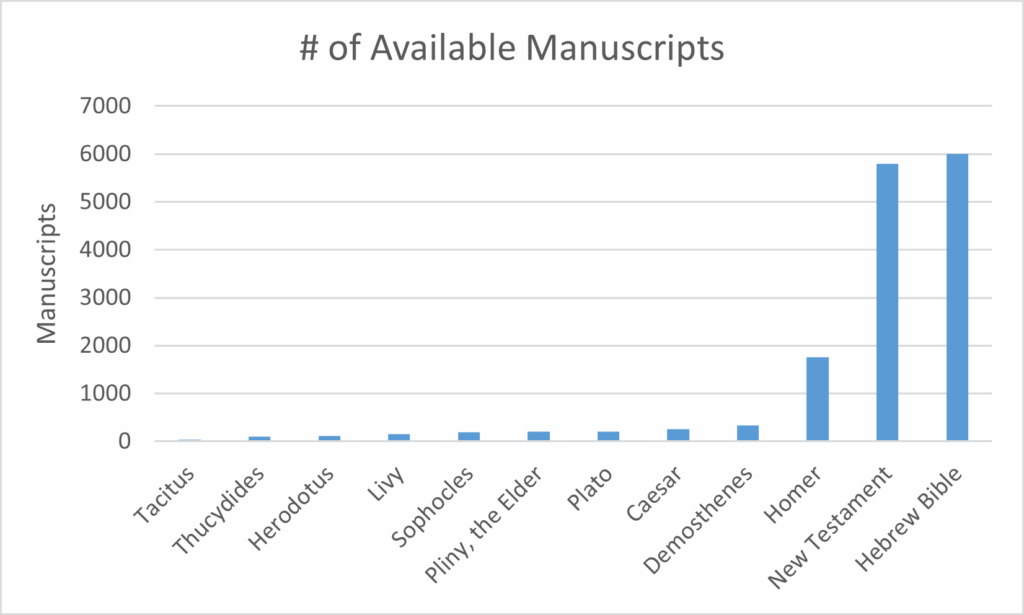

As this table indicates, the New Testament’s textual evidence far outperforms other works in antiquity.[53] Here is the table in chart form:

Figure 4 – Time Gap to the Earliest Manuscript of Notable Ancient Works

If one believes that the bigger the time gap, the more one ought to be skeptical of the text, then one ought to be less skeptical of the New Testament than most texts taught in the Classics department. Conversely, if one has not considered the integrity of works by Plato, Homer, Tacitus, and others, then intellectual consistency would encourage giving the New Testament the benefit of the doubt as well. As the Torah requires, we must use equal weights and measures when making determinations (Lev. 19:36).

New Testament textual scholar Daniel Wallace comments:

How does the average Greek or Latin author stack up [to the New Testament]? If we are comparing the same time period—300 years after composition—the average classical author has no literary remains. But if we compare all the MSS [manuscripts] of a particular classical author, regardless of when they were written, the total would still average at least less than 20 and probably less than a dozen—and they would all be coming much more than three centuries later. In terms of extant MSS, the NT [New Testament] textual critic is confronted with an embarrassment of riches. If we have doubts about what the autographic [original] NT said, those doubts would have to be multiplied a hundredfold for the average classical author. When we compare the NT MSS to the very best that the classical world has to offer, the NT MSS still stand high above the rest. The NT is by far the best-attested work of Greek or Latin literature from the ancient world.[54]

The time gap between composition and manuscript is crucial, but this must also be coordinated with the number of total manuscripts known to scholars today. The more manuscripts of a document available, the easier it is to spot outliers. If we only have two or three manuscripts available from the same era, and they disagree with each other about a particular word or phrase, then it is very difficult to figure out which one is correct. But what if we have more than 5,800 manuscripts to compare with each other, and we know the dating of each? The outliers jump off the page!

The New Testament and the Hebrew Bible are uncontested champions concerning the number of surviving manuscripts available today. There is truly no other ancient document like them. Below is a recent tally[55] of the manuscripts of the same list of ancient works for comparison:

| Author | Work | # of Manuscripts |

|---|---|---|

| Homer | Iliad | 1,757 |

| Herodotus | History | 109 |

| Sophocles | Plays | 193 |

| Plato | Tetralogies | 210 |

| Caesar | Gallic Wars | 251 |

| Livy | History of Rome | 150 |

| Tacitus | Annals | 33 |

| Pliny, the Elder | Natural History | 200 |

| Thucydides | History | 96 |

| Demosthenes | Speeches | 340 |

| Various | New Testament | 5,795[56] |

| Various | Hebrew Bible | 6,000[57] |

Sometimes, a chart speaks louder than a table:

Figure 5 – Number of Available Manuscripts of Notable Ancient Works

The Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are off the charts! There are more manuscripts available for them than for all the others combined. The only comparable ancient work is Homer’s Iliad, which is a distant third. However, the numbers given above only account for New Testament manuscripts written in Greek, its original language. If we were to add the 15,000+ ancient manuscripts of the New Testament translated into other ancient languages,[58] such as Latin, Ethiopic, and Syriac, there would be no contest.

What do we learn from this analysis? Precisely this: The New Testament has the strongest manuscript support of any ancient work in existence. It is stronger even than the Torah, as the time gap between autograph and surviving manuscript is in the region of decades, rather than millennia. If one thinks there is good manuscript evidence to trust in the accuracy of the text of the Hebrew Bible, then one has even better evidence for the text of the New Testament. Believing in the integrity of either takes a leap of faith, because we do not have autographs penned by Moses, the Prophets, or the Apostles. However, the leap of faith is much shorter in the New Testament’s case because of its rich manuscript tradition.

As distinguished Hebrew textual critic Emanuel Tov of Hebrew University writes, “[T]here is less divergence among the various NT sources than that seen among the witnesses [manuscripts] of Hebrew-Aramaic Scripture.”[59] If the New Testament has more textual reliability than even the Tanakh, that is really saying something![60]

External Evidence #2: Quotes in Other Works

The early believers in Yeshua quickly adopted the books of the New Testament for use in corporate worship services. We have thousands of pages of books written by these early believers (also known as the “church fathers”), and they quoted extensively from the New Testament. In fact, scholars could reconstruct the majority of the New Testament using only the quotations embedded in second- and third-century Christian works. Scholars could also do the same thing with the Torah, assuming we had only the Talmud available, since the Sages quoted from the Torah so often.

Imagine we have the work of a certain author that dates to around 95 CE, and in that work, the author quotes from the Gospel of Matthew. The Gospel of Matthew, then, could not have been written later than 95 CE, for it had to preexist to be quoted in another author’s work. This is the exact scenario we have with the First Epistle of Clement, who in chapter 46, verse 8, quoted from Matthew 26:24. Also, 1 Clement 13:2 stringed together quotations from both Matthew and Luke. In fact, Clement’s first letter referred to many books in the New Testament, so none of them could have been written later than 95 CE.

The Didache, an early Messianic Jewish immersion manual circa 100 CE, provides another example of an early quotation of a New Testament book. It was the product of a Messianic Jewish community, just as most of the New Testament books were. It liberally uses text from the Gospel of Matthew in its instructions to new believers. The Gospel of Matthew, then, must pre-date the writing of the Didache.

Circa 150 CE, Justin Martyr wrote, “For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them.”[61] From this we learn that Justin was aware of at least two Gospels, since he used the plural Gospels. But which Gospels did he know of? We can find direct quotations of Matthew[62], Luke[63], and John[64] in Justin’s writings. Since Matthew and Luke likely relied on Mark, it is evident that all four Gospels were circulating around the time of Justin Martyr.

Therefore, an important principle to remember is that New Testament books cannot be later than the works that quote them.

External Evidence #3: Early Reports by Christian Writers

Soon after the Jewish apostles of Yeshua published their Gospels and letters, other believers started talking about them. Some of them wrote descriptions of the New Testament books and included information about dates and authorship. This is a different class of external evidence than the previous section, for the previous section talked about explicit quotations of New Testament works, whereas this evidence does not include quotes.

One of the earliest reports comes to us from Papias, who was a disciple of the apostle Yohanan, commonly known as John.[65] Other reports come from Clement, Ignatius, Tertullian, and the Marcionite Prologues—all dating from the second century. We handled some of these reports in the previous discussion on external evidence for authorship. These testimonies are important and must be considered when determining the dates of authorship of the books of the New Testament.

Thus, after surveying the internal and external evidence for the dating of the books of the New Testament, we find first-century CE dates for the composition of the texts to be more congruent to the evidence. Moreover, we believe that a pre-70 CE date for most of the New Testament fits the evidence more adequately than theories that postdate the Temple’s fall. Of course, we are speaking here in broad strokes, and each book of the New Testament should be handled individually when considering dating. We have given a closer look at books such as Acts and 1 Corinthians in this article, but each book could have its own lengthy discussion. For such a discussion, we recommend An Introduction to the New Testament by D.A. Carson and Douglas Moo.[66]

Addressing Objections to the New Testament

Despite the historical accuracy of the New Testament accounts, some have found reason to doubt its claims for various reasons. Elsewhere on this site we have articles dealing with supposed antisemitism in the New Testament, why some books were included in the New Testament and not others, and other important topics. However, for the rest of this article, we will address specific objections related to the New Testament’s dating and authorship.

Isn’t Even a Gap of a Few Decades from Yeshua’s Death Room for Error?

In the discussion above, we have made a case for early dates for the New Testament books, all within the first century, and mostly around the 50s and 60s CE. But even this, some may say, is still twenty to thirty years removed from the events of Yeshua’s life in the 30s. How can we trust these works when they have such a time gap? Would we trust someone’s detailed recollection today about conversations and sequences of events that occurred in 1990, when we have no other way of verifying what they say?

To begin with, that question has a faulty premise. For one, 1990 was not very long ago, and there could still be living eyewitnesses, scraps of paper, geographical locations, and even audiovisual recordings that could corroborate the claims about the 1990 events. Second, a 30-year time gap is no hinderance to recollection when (1) the event was emotionally charged, or (2) there exists some mechanism to aid memory.

For example, many Baby Boomers can remember the time, place, and action they were performing when they heard about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The circumstances of the September 11, 2001 attacks on New York are similarly seared into many who were alive at the time. These were emotionally charged events that most mentally healthy people cannot possibly forget. Likewise, watching videos, hearing audio recordings, and viewing photos of events from 30 years ago can unleash a flood of memories, serving as mechanisms for remembering the past.

However, first-century Jewish culture was not the same as our own. They had different mechanisms for remembering the past, including one that is difficult for us modern people to understand: oral memory. It is difficult for us to understand the power of oral memory because we rarely have to use that part of our brains: we are dependent upon the written word, not the oral!

For example, before cell phones and contact apps, most people memorized the phone numbers of close friends and family due to sheer repetition. We had to type in each number individually or spin a rotary dial! As a child who grew up during this era, I can still remember my best friend’s phone number from second grade. Today, I am completely dependent upon my cell phone’s contacts app, and therefore I can barely list off any friends’ or family members’ numbers. I have lost the skill of memory that I once had.

We need to put ourselves in the shoes of first-century Jewish people, even if their culture and ways of thinking were foreign to our own. First-century Jewish people, which included Yeshua’s earliest followers who composed the Gospel accounts about his life, lived and breathed in an oral culture where the written word was difficult to access. Access to the written texts of Scripture was limited to synagogues and the Temple, so common people learned the Scriptures and other blocks of information through memorization. New Testament scholar Craig Blomberg, who specializes in Second Temple Judaism, discusses this phenomenon:

How was such memorization possible? First, it was an oral culture not dependent on all the print media that dominate our modern world. Second, the main educational technique employed in schools was rote memorization. Jews even had a tradition that until a boy had memorized a passage of Torah, he was not qualified to discuss it lest he perhaps misrepresent it. Third, in Jewish circles, “Bible” was the only subject students studied during the fairly compulsory elementary education that spanned ages five to twelve or thirteen, and that took place at least wherever there were large enough Jewish communities to have a synagogue. Fourth, memorization thus began at the early ages when it is the easiest period of life to master large amounts of content. Fifth, texts were often sung or chanted; the tunes helped students remember the words, as they do with contemporary music too. Finally, a variety of other mnemonic devices dotted the texts that were studied so intensely. Especially crucial in the Jewish Scriptures were numerous forms of parallelism between lines, couplets and even larger units of thought. In this kind of milieu, accurately remembering and transmitting the amount of material found in one Gospel would have been comparatively easy.[67]

In light of this oral culture, we can conclude that Yeshua’s disciples had an ever-present mechanism to assist their memory: their own heightened ability to memorize, which could be cross-checked with others and mastered in unison. In addition, the events they narrated, principally the crucifixion and resurrection of Yeshua, were emotionally charged events that Yeshua’s followers could not have possibly forgotten. However, we would be remiss to leave this discussion solely in the realm of natural or secular causes. The New Testament itself, take it or leave it, records that Yeshua would send God’s Holy Spirit to aid the disciples’ memory of what Yeshua said and did (John 14:26; 2:22).

In the midst of an oral culture with living eyewitnesses, a time gap of 30 years (at most) to the earliest Gospel is no true obstacle. In fact, if this time gap were to be an obstacle, then we would have to conclude that nothing can be known about history at all. Why? If the New Testament cannot withstand a gap of 30 years to composition, and 40 years to the earliest manuscript (of John), then no historical work in the world’s museums and libraries should be trusted. Blomberg continues,

We are speaking of documents compiled about fifty years or less after the events they narrate. In our age of instant information access, this can seem like a long time. But in the ancient Mediterranean world, it was surprisingly short. The oldest existing biographies of Alexander the Great, for example, are those of Plutarch and Arrian, hailing from the late first and early second centuries c.e. Alexander died, however, in 323 b.c.! Yet classical historians regularly believe they can derive extensive, reliable information from these works to reconstruct in some detail the exploits of Alexander.[68]

Why do historians believe they can derive reliable information about Alexander from biographies written 400 years after his death? That is a good question for the Classics department at a local university. But for our purposes, we have an even smaller gap when it comes to the biographies of Yeshua’s life.

What if the New Testament Is Just Historical Fiction?

The historical details included within the New Testament align with what we know of pre-70 CE Jewish life in Judea. These include geographical, linguistic, archaeological, and chronological details that are corroborated in sources outside of the writings of Yeshua’s followers. If the New Testament claims to be a record of history, then these historical details might appear to support that claim.

But what if those details are irrelevant, because the New Testament is just historical fiction—books that appear to be true, but are no more true than a novel? The nineteenth century novel Ben-Hur by Lew Wallace comes to mind—the story that was immortalized in Charlton Heston’s 1959 film. Wallace’s fictional story, subtitled, “A Tale of the Christ,” contained historically believable details about Roman and Jewish culture, place names, social customs, and the rest. It even included scenes where the protagonist, Judah Ben-Hur, interacted with Jesus in events recorded in the Gospels. Everyone knows that Ben-Hur was fiction, and its historical details do not make it less fictional. Why can’t the same be said about the New Testament?

John R. Morgan, the former leader of the Kyknos Research Group on Ancient Narrative Literature, has written an essay entitled, “Fiction and History: Historiography and the Novel,” in which he discusses how one can distinguish historical fiction from historical narrative in ancient Greek literature. Morgan cautions, “Above all, we must be careful, in reading both ancient fiction and ancient historiography, not to impose our own preconceptions on them.”[69]

He notes that while there were fictional plays (tragedies, comedies) in Greek and Latin culture, the first western “novel” was Chariton, which dates to the first century CE. Chariton was not meant for the stage, but for private reading, and as such it was a completely new genre of literature. Did its readers fall into the gullible trap of believing the novel was true, or did they make an uproar that the book was telling lies? Neither, Morgan says. Both the reader and the author knew what was going on, as a kind of contract to allow for untruths:

Greek novels, pretty well without exception, strive, then, for historiographical authority and authenticity, for believability. However, the defining condition of any fiction is that it is an untruth which does not intend to deceive. Fiction is neither truth nor lie: both sender and recipient recognize it for what it is. No ancient reader with a copy of Chariton in his or her hand can seriously have thought that he or she was holding a work of history, or that the events narrated in it had really taken place. How can anyone be said to believe something which they know to be untrue? Coleridge’s famous phrase to explain this paradox is “the willing suspension of disbelief.” One way to describe the phenomenon of reading fiction is in terms of a conspiracy or contract between text and reader, that, in order to experience the full pleasure of the text, the reader should imaginatively “believe” the truth of what he is reading even while remaining intellectually aware of its fictional status.[70]

Thus, an essential element of ancient historical fiction was a kind of agreement between the author and the reader that entailed suspending disbelief for pleasure. As an example of this agreement, Morgan cites a prologue from the second-century CE novelist Lucian of Samosata, who proclaimed that his novel True Histories was, in fact, all lies. However, this was not understood to be a moral failure, since Lucian had no intent to deceive, and his audience was not deceived either.

The church father Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE), himself familiar with the Greco-Roman culture of playwrights and novelists, reflected on the moral status of fictional works. He commented,

[N]ot every one who utters falsehood, wishes to mislead; for both mimes and comedies and many poems are full of falsehoods, rather with the purpose of delighting than of misleading, and almost all those who jest utter falsehood. But he is rightly called fallacious, whose purpose is, that somebody should be deceived.[71]

How can this information help determine the answer to whether the New Testament was merely historical fiction? We will primarily address this topic in relation to the Gospels and Acts, which are the most narrative-focused books in the New Testament.

First, there is no historical evidence that the Gospels or Acts were ever understood by early readers to be fiction, not even by non-mainstream groups. It appears that all groups interested in Jesus in the first and second centuries accepted one or more Gospels as true. Of course, the mainstream orthodox church accepted all four Gospels as authentic. In the second century, the Ebionites accepted the Gospel of Matthew in Hebrew, and arch-heretic Marcion accepted Luke. The second-century Gnostic Valentinians accepted and reinterpreted the New Testament canon in their Gospel of Truth.[72] If the major feature of historical fiction is an author-audience agreement upon the fictional status of the work, no one seems to have entered that agreement.

Second, the kind of historical fiction that the Gospels have been accused of was not at all common in the first century CE. Although bookshelves in today’s bookstores may be full of fiction, that was not the case in first-century Judea. Jewish audiences were familiar with pseudepigraphal books, which were fictional books written in the name of Israel’s revered forebears, such as Adam, Moses, or Enoch.[73] However, pseudepigraphal books were separated from their purported authors by centuries or millennia; none were stories about contemporary events. The Gospels and Acts, in contrast, claim to narrate contemporary events that were written—assuming a very skeptical late date—no more than 100 years after the events described. If one holds that the Gospels and Acts are historical fiction, one must come up with a theory for how three Jewish authors (Matthew, Mark, and John) and one Gentile author (Luke) could be so innovative to develop five books of historical fiction with little precedent.

Third, a major feature of ancient fiction writing was the element of pleasure that it gave to the reader. It is unclear how this could apply to the narrative-based New Testament books. How is reading about a man’s crucifixion “pleasure reading”? Moreover, the Gospel of Mark famously ended abruptly with only a brief mention of Yeshua’s resurrection, and no commentary on what his resurrection could mean to the reader.[74] The Gospels include many passages that accuse and challenge the reader (e.g. Matt. 5:22, 5:28), rather than evoking comfort. The purpose of the New Testament, unlike historical fiction, appears to be something other than pleasure.

Fourth, we cannot divorce the central details of the Gospels and Acts far enough away from history to be credibly called historical fiction. Most of the primary characters of the New Testament were still alive when the books were published. For example, in the creed in 1 Corinthians 15:3–8, individual followers of Yeshua like Peter (Cephas), James, and Paul are mentioned as witnesses of Jesus’ resurrection, as well as more than 500 unnamed others, who are claimed to be still alive, although some had died already. These same characters appear in the Gospels and Acts, where they are described as eyewitnesses of the things recorded. An author writing fiction cannot play off these claims as fictional while the real people are still alive, at least not without an uproar over their slander. But the real people mentioned in the accounts never made such an uproar—instead, they promoted the message of the accounts.

In sum, we do not believe that the abundant number of accurate historical details in the New Testament may be explained away as historical fiction. This claim is employed to give tacit admission to the accuracy of New Testament historiography, while enabling continued rejection of the New Testament’s religious and supernatural truth claims. We do not believe this tactic works; because the Gospels and Acts are not historical fiction, the accurate historical details within them should lead readers to consider that the books’ supernatural truth claims should be taken seriously.

The Forgery Hypothesis: Time to Leave it Behind

In light of the previous evidence for the authorship and dating of the New Testament, it is not reasonable to accuse the New Testament of being a forgery. To accurately call something a forgery, one needs to demonstrate an intent to deceive. If the authors of the New Testament intended to deceive their audiences, they did so in an incredibly sophisticated way:

We maintain that these accusations of bad motives are implausible. We must heap on conspiracy conjecture after conspiracy conjecture in order to justify denying the evidence in favor of the New Testament’s authenticity. If the New Testament is a forgery, then the authors of the New Testament are the most devious, scheming, and devilishly dishonest (yet successful) conspirators in history. If one believes the New Testament authors forged the documents, one needs to provide credible evidence of motive. Such a motive remains elusive.

Conclusion

In light of all that has been discussed above, when we open up the books of the New Testament, we find the writings of authors who claimed to walk with, talk with, and eat with Yeshua of Nazareth. They were eyewitnesses of his life and death, and they even claimed to be eyewitnesses of his resurrection. The books of the New Testament are important, definitively Jewish, and are demonstrably early accounts of the events they record. Both internal evidence (geographical, historical, linguistic) and external evidence (manuscripts, quotations, reports) point in this direction.

The books of the New Testament cannot be dismissed easily. They deserve a second look by all Jewish people who have believed negative things about them. We encourage you to open up the New Testament afresh today.

Bibliography

Armstrong, W. P., and J. Finegan. “Chronology of the NT.” In The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised, edited by Geoffrey William Bromiley, 1:1:686-93. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1979–1988.

Barnett, Paul. The Birth of Christianity: The First Twenty Years. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005.

Bauckham, Richard. Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Second Edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2017.

Blomberg, Craig. “Jesus of Nazareth.” In Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, by Douglas Groothuis, 438–74. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic; Apollos, 2011.

Blomberg, Craig L. Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey. 2nd Edition. Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2009.

Bock, Darrell L. Acts. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007.

“Bodleian Library MS. E. D. Clarke 39,” 2018. https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/95494680-e747-49a7-8080-36e0261e0640/.

Boyarin, Daniel. “Beyond Judaisms: Metatron and the Divine Polymorphy of Ancient Judaism.” Journal for the Study of Judaism: In the Persian Hellenistic & Roman Period 41, no. 3 (July 2010): 323–65.

———. “Enoch, Ezra, and the Jewishness of ‘High Christology.’” In Fourth Ezra and Second Baruch, edited by Matthias Henze and Gabriele Boccaccini, 337–61. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013.

———. The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ. New York, NY: The New Press, 2012.

———. “Two Powers in Heaven: Or, the Making of a Heresy.” In The Idea of Biblical Interpretation, 331–70. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2004.

Bruce, F. F. The Canon of Scripture. Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, 1988.

Carson, D. A., and Douglas J. Moo. An Introduction to the New Testament. Second Edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005.

Charlesworth, James Hamilton, ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1983–1985.

Crawford, Brian J. The Scandal of a Divine Messiah: A Reassessment of Maimonidean and Kabbalistic Challenges to the Incarnation. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2024.

Geisler, Norman L. Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1976.

Gilbert, Gary. “The Acts of the Apostles.” In The Jewish Annotated New Testament, edited by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, First. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Hengel, Martin. Studies in Early Christology. New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2004.

Hurtado, Larry W. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003.

Jews for Judaism. “The New Testament and Its Inconsistencies,” June 22, 2009. https://jewsforjudaism.org/knowledge/articles/the-new-testament.

Jones, Clay. “The Bibliographical Test Updated.” Christian Research Institute (blog), April 12, 2023. https://www.equip.org/articles/the-bibliographical-test-updated/.

Keener, Craig S. Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2019.

Kinzig, Wolfram. “The Nazoraeans.” In Jewish Believers in Jesus: The Early Centuries, edited by Oskar Skarsaune and Reidar Hvalvik, 463–86. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007.

Köstenberger, Andreas J., and Michael J. Kruger. The Heresy of Orthodoxy: How Contemporary Culture’s Fascination with Diversity Has Reshaped Our Understanding of Early Christianity. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010.

Lapide, Pinchas. The Resurrection of Jesus: A Jewish Perspective. Translated by Wilhelm C. Linss. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2002.

Levine, L. I. “Jewish War.” In The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 3:3:839-45. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992.

Licona, Michael R. The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2010.

McDonald, Lee Martin. “Anti-Marcionite (Gospel) Prologues.” In The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 1:1:262-63. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992.

Morgan, John R. “Fiction and History: Historiography and the Novel.” In A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography, edited by John Marincola, 1131–54. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2017.

Neusner, Jacob. The Mishnah: A New Translation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988.

Nolland, John. The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Grand Rapids, MI; Carlisle: W.B. Eerdmans; Paternoster Press, 2005.

Norman, Asher. Twenty-Six Reasons Why Jews Don’t Believe in Jesus. Los Angeles, CA: Black White & Read, 2008.

Oliver, Isaac. “Isaac Oliver Reviews The Ways That Often Parted.” In Reviews of the Enoch Seminar. Enoch Seminar Online, 2019. http://enochseminar.org/review/16141.

Pearse, Roger. “The ‘Anti-Marcionite’ Prologues to the Gospels.” The Christian Classics Ethereal Library, 2006. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/pearse/morefathers/files/anti_marcionite_prologues.htm.

Schäfer, Peter. Two Gods in Heaven: Jewish Concepts of God in Antiquity. Translated by Allison Brown. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Schaff, Philip, ed. St. Augustin: Homilies on the Gospel of John, Homilies on the First Epistle of John, Soliloquies. Vol. 7. New York: Christian Literature Company, 1888.

Schnabel, Eckhard J. “The Muratorian Fragment: The State Of Research.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 57, no. 2 (2014): 227–64.

Segal, Alan F. Two Powers in Heaven: Early Rabbinic Reports about Christianity and Gnosticism. Reprint. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2012.

Stark, J. David. “Semitisms in the New Testament.” In The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Thiselton, Anthony C. The First Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 2000.

Tov, Emanuel. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. 3rd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2012.

Wilcox, Max. “Semiticisms in the NT.” In The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 5:5:1081-86. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992.

Witherington, Ben, III. The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1998.

Footnotes

- For an extensive academic discussion of the biographical genre of the Gospels, see Craig S. Keener, Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2019). Acts is a historical book that includes biographical elements for two of its primary characters, Peter and Paul. ↑

- The letters included in the New Testament fall under several genres. Some letters were intended for congregational use (i.e., Romans, 1 Corinthians), others were personal letters to individuals (i.e., 1 Timothy, 2 John), and Revelation is in its own category as an apocalyptic work with a series of letters included within. ↑

- With the possible exception of the author of Luke and Acts. Paul appears to classify Luke as non-Jewish in Colossians 4:11–14. ↑

- See below for further discussion of this point. Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2017). ↑