Introduction: The Story of the Septuagint

According to an ancient Jewish legend recorded in the Letter of Aristeas (written by a Hellenistic Jew in the second century BCE), the Egyptian king Ptolemy II (285–247 BCE) summoned seventy-two Jewish elders to translate the famous Jewish Torah into Greek.[1] The Greek general Alexander the Great had conquered the Mediterranean basin in the fourth century, and the Greek rulers after him undertook an extensive project of translating the great works of the peoples of the world into Greek to be stored in the famous Library of Alexandria.[2] In Aristeas 38–39, it is reported that Ptolemy II issued the following decree:

We have accordingly decided that your Law shall be translated into Greek letters from what you call the Hebrew letters, in order that they too should take their place with us in our library with the other royal books. You will therefore act well, and in a manner worthy of our zeal, by selecting elders of exemplary lives, with experience of the Law and ability to translate it, six from each tribe, so that an agreed version may be found from the large majority, in view of the great importance of the matters under consideration.[3]

This is the origin story of the original Greek translation of the Torah of Moses.[4] This translation is now known as the Septuagint, a Greek name for “seventy,” referring to the round number of Jewish sages who produced the translation. In scholarship, the Septuagint is often abbreviated as LXX, the Latin number for seventy.

This origin story of the Greek version of the Torah was widely accepted in the ancient world. It was repeated by the Jewish historian Josephus[5] (first century), the Jewish philosopher Philo[6] (first century), the sages of the Talmud (third–sixth centuries),[7] and many Christian writers.[8] It was common for both Jewish and Christian writers to affirm the authority and accuracy of the Septuagint, and some went so far as to affirm its divine inspiration on par with the Hebrew originals.[9]

After this first translation of the Torah into Greek, unknown Jewish translators proceeded to translate the rest of the Hebrew Bible into Greek for the next century. By the second century BCE, the entire Tanakh had been translated into Greek, and the books found widespread use throughout the Jewish world, which was increasingly dependent upon the Greek language. Although in one sense it is true that only the original translation of the Torah may be called, “the Septuagint,” the name was later expanded to include all the old Greek translations of the Prophets and Writings that were in common use in Judaism.

In this article, we will follow the common scholarly convention of using the name “Septuagint” to describe the Greek versions of the Torah, Prophets, and Writings that were used by Jewish people during the Second Temple period, while also recognizing that the name originally only described the five books translated by the seventy-two elders. In addition, we recognize that there is no one “Septuagint,” but rather a family of manuscripts with the title. Like most works of antiquity, we do not have the original autograph manuscripts of the Septuagint translations, but rather copies of them. Modern scholars use sophisticated tools to determine which manuscripts better reflect the original Greek translations than others.[10]

During the first century CE, a Jewish man named Yeshua (Jesus) started preaching about the kingdom of God and how he was the promised Jewish Messiah. When Yeshua’s followers started writing down the things he said and did—and explained the implications of his identity—they wrote in Koine (common) Greek. This was entirely normal for first-century Jews, as Greek was the common language of the day for Jewish people—with many even forgetting the use of Hebrew.[11] Also, in common with other Jewish authors of the day, Yeshua’s followers quoted from the Jewish Scriptures, and when they did so, they often quoted from the Greek Septuagint. Thus, the writings of the New Testament include quotations of the Jewish Bible, but those quotations were often sourced from the Greek translations that were available at the time, which we now collectively call the Septuagint.

However, as the message of Yeshua spread throughout the world by Jewish and Gentile messengers, some Jewish people—as we will see below with Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus—took issue with the New Testament’s use of the Jewish Bible. Thus, while Yeshua-followers and their opponents were arguing about Yeshua’s messianic status, the authenticity and authority of the Septuagint became a matter of intense debate. Whereas before, the Septuagint was largely uncontroversial in Jewish circles, starting in the second century CE, it became a battleground in the discussion about the messiahship of Yeshua.

In this contest over the texts, several passages became contentious. The most prominent disagreement was the identity of the woman described in Isaiah 7:14.[12] The Septuagint said “parthenos,” a young woman who had never had sexual relations, whereas the Hebrew said “almah,” a woman of marriageable age who may or may not be a virgin.[13] Jewish and Gentile followers of Yeshua could often point to the Septuagint for their preferred interpretation, saying that pre-Yeshua Jewish people had supported their beliefs. Thus, the Septuagint enabled Jewish and Gentile followers of Yeshua to cite a respected Jewish source to combat the objections of contemporary Jewish people. However, the controversy was not confined to the Isaiah verse alone. Other controversial passages included:

In general, because these verses in the Septuagint seemed to lend credibility to the arguments of the Jewish followers of Yeshua and Gentile Christians, many second-century Jewish people sought to distance themselves from the Septuagint. Starting in the second century CE, we see the Septuagint come under criticism in Jewish circles for the first time. Initially, this criticism resulted in the production of new Jewish translations of the Scriptures into Greek, namely the translations of Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus (often called, “the Three”).[15] These Jewish translators, to varying degrees, attempted to align their translations with the Hebrew text available to them at the time, and sometimes they translated in such a way to undermine the New Testament’s use of the Septuagint.

However, these three translations never found widespread popularity in Judaism because Jews started distancing themselves from the Greek language in general. Whereas Greek was the lingua franca of the world for centuries, including for Jewish people, after the destruction of Jerusalem and exile in 70 CE, the use of Greek began to decline. After the third century CE, with the widespread proliferation of the Mishnah, Gemara, and the Targums, all in Hebrew or Aramaic, Jewish people regained their proficiency in Semitic languages and largely refrained from using Greek translations of the Scriptures.[16]

Thus, several centuries after the coming of Yeshua, the Septuagint fell out of use in Jewish circles, and became associated with Christianity. A set of translations that had originally been produced by Jewish people, and quoted in the New Testament (also of Jewish authorship), was now, ironically, associated with Gentiles. Likewise, other Greek-language books by Jews that quoted from the Septuagint, such as Philo and Josephus, were only used by Christians until the Enlightenment. Whereas it was a Jewish thing to quote the Septuagint in the first century, it became seen as Gentile and Christian to cite the Septuagint within a few centuries. Despite the Septuagint’s importance for the New Testament, many Christians today are unfamiliar with the Septuagint and its history. Because very few know Greek, the Septuagint is foreign territory. The unfamiliarity runs deeper in the Jewish world, where anything “Greek” is often viewed as “non-Jewish.” Moreover, much of the Septuagint’s history is complicated and laden with unknowns. Readers are recommended to review the entry on the Septuagint in the second edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica to be introduced to the complexities of the subject by a knowledgeable Jewish scholar.[17] Septuagint scholars debate as to who translated each book, and when, and the relationship of various Greek manuscripts to one another and to the text families of the Qumran and Proto-Masoretic scrolls.[18] Much can be known about the Septuagint, but attaining such knowledge requires a high level of historical and linguistic education.[19] Because there is widespread ambiguity and unfamiliarity regarding the Septuagint, it is a topic that is ripe for speculation and exploitation for partisan gain.

Rabbi Tovia Singer’s Claims of a Christian Conspiracy

Rabbi Tovia Singer, a determined opponent of Yeshua and the claims of the New Testament, has made attacks on the Septuagint a key part of his arguments against the New Testament. By sowing doubt on the integrity of the Septuagint, he seeks to undermine belief in Yeshua. Whereas the typical wisdom would be to ask, “How did the Septuagint influence the New Testament?,” Singer flips the logic around. He writes, “The Christian editors of the Septuagint retrofitted and shaped [it] so that it would comport with Matthew’s mistranslation of Isaiah 7:14; not the other way around.”[20] When discussing the Septuagint, Singer calls it a “theological crime scene.”[21] In a key passage, he says, “The Septuagint that is currently in our hands—especially the sections that are of the Prophets and Writings—is a Christian work, doctored and edited exclusively by Christian hands.”[22]

He explains his reasoning as follows:

It is universally conceded, and beyond doubt that the rabbis who created the original Septuagint only translated the Five Books of Moses, and nothing more. This undisputed point is well attested to by the Letter of Aristeas, the Talmud, Josephus, the Church fathers, and numerous other critical sources….

Furthermore, even the current Septuagint of the Five Books of Moses is almost entirely a complete corruption of the original Greek translation that was compiled by the 72 rabbis more than 2,200 years ago at the request of King Ptolemy II of Egypt. This fact is well known to us because the Talmud records how these 72 translators distinctly rendered 15 phrases of the Torah in their translation. Of these 15 unique translations, only two are extant. It’s clear that the Septuagint’s version of the Torah is a corruption of the original translation made by the 72 Jewish scribes. In addition, the rest of the Septuagint is a translation by Christian scholars with a strong motive to twist the messages of the Jewish Bible.[23]

Elsewhere, he writes,

Moreover, the Septuagint in our hands is not a Jewish document, but rather a Christian recension…. In essence, the present Septuagint is largely a post-second century Christian translation of the Bible, used zealously by the Church throughout its history as an indispensable apologetic instrument to defend and sustain Christological alterations of the Jewish Scriptures…. In essence, there were numerous Greek renditions of the Jewish Scriptures which were revised and edited by Christian hands. All Septuagints in our hands are derived from the revisions of Hesychius, as well as the Christian theologians Origen and Lucian. Accordingly, the Jewish people never use the Septuagint in their worship or religious studies because it is recognized as a corrupt text.[24]

As is evident from Singer’s own words, he believes the Septuagint is a Christian conspiracy to undermine the Hebrew Scriptures through twisting texts to back up Christian theology. Besides his written work on his website, Singer has promoted this view of the Septuagint on his YouTube channel on multiple occasions[25] and in his printed books,[26] and others have repeated his claims.[27]

A Summary of Singer’s Claims

In his arguments against the Septuagint, Rabbi Tovia Singer makes a variety of points. For clarity’s sake, we will summarize his points below.

Regarding the Torah

Regarding the Prophets and the Writings

As we continue in this article, we will assess each of these claims. While we agree in full with one of them (No. 2), we believe that the rest of Singer’s points are false or only partially true, and can be shown as such with historical and textual evidence.[28]

Some Initial Affirmations and Agreements with Rabbi Singer

Before proceeding into a critique of Tovia Singer’s position, let us begin by giving him credit where it is due.

First, it is true that the original translation of the Jewish Bible into Greek consisted of a translation of the five books of Moses alone. The earliest account of the translation available, the Letter of Aristeas, only mentions the five books being translated, and the subsequent reports of Aristobulus, Philo, Josephus, and the Talmud agree: The 72 translators only translated the Torah.

Second, Singer correctly identifies a linguistic ambiguity when referring to the Septuagint. He is correct in saying that the name, which means “seventy (two),” if being overly precise, should only be used to describe the translations of the 72 translators—that is, the five books of Moses into Greek. The 72 were not responsible for translating the Psalms, for example, so it would be a technical misnomer to call the Psalms part of the Septuagint. However, this is a misnomer only if one’s goal for linguistic precision is uncommonly high, and common practicality is ignored. As with many words, the term “Septuagint” expanded in meaning over the centuries to encompass both the Greek Torah and the Greek Prophets and Writings.

While this verbal ambiguity may be confusing to laypeople who know little about the Septuagint, scholars of the Septuagint are well aware of the 72 not being responsible for the translation of the Prophets and Writings. However, by convention and based on the expanded meaning, scholars still use the term “Septuagint” to describe all of the pre-second-century Greek versions of the Greek Bible. As the Encyclopaedia Judaica simply states, “[T]he Pentateuch was translated into Greek in Alexandria during the first half of the third century B.C.E. The designation Septuagint was extended to the rest of the Bible and the noncanonical books that were translated into Greek during the following two centuries.”[29]

Third, we applaud Singer’s defense of the integrity of the Hebrew Scriptures, and we affirm that the Masoretic text manuscripts ought to have primacy of place when it comes to the text of Scripture. We, too, believe that the Masoretic is usually a more trustworthy source for reading the Tanakh. In our article “Textual Criticism 101,” we have laid out the reasons for this judgment. However, we come to our belief in the importance of the Masoretic text from a different angle than Tovia Singer.

Responding to Singer: Two Lines of Questioning

As we chart a course to respond to Tovia Singer’s claims about the Septuagint, we will investigate two lines of questioning that address most of his claims.

First, did Jewish people translate the Prophets and the Writings into Greek before Yeshua’s time? Singer never investigates this question but rather states that Christians were either responsible for 1) translating the Prophets and Writings or 2) editing or doctoring or corrupting the Prophets and the Writings. The inconsistency between these two options is telling, because it enables him to cast doubt on the Septuagint of the Prophets and Writings while never being clear on who did the original translation work. His two positions can be classified as a “hard” and a “soft” claim. The hard claim states that Christians were responsible for translating the Prophets and the Writings for the first time, and Jews had never done so before. The soft claim is that Christians took an already-existing translation of the Prophets and Writings, presumably translated by Jews (although Singer never explicitly states this), which Christians subsequently corrupted.

Second, did Christians corrupt the Greek translations after Yeshua’s time? Singer clearly says yes; whatever the origin of the translations, the ones that we have in manuscript today are corrupt and were doctored by conspiratorial Christian copyists. Singer cites two lines of reasoning for his position. First, he cites the Talmud’s reporting of fifteen passages where the “real” Septuagint differed from the Hebrew. Because the Talmud’s reporting cannot be matched with any known Greek version in thirteen of the instances, Singer concludes that the Septuagint we have today is corrupt. He cites no manuscripts that illustrate a before-and-after corruption process, besides that in the Talmud. Second, Singer cites translation flashpoints like “parthenos” in Isaiah 7:14 as something no Jew would ever accept, and if no Jew would translate “almah” as “parthenos,” then certainly a Christian must have done it.

Let us now investigate these questions with a proper historical, textual, and linguistic analysis.

Did Jewish People Translate the Prophets and Writings into Greek Before Yeshua’s Time?

When we investigate the origin and authorship of the Greek versions of the Prophets and the Writings, we find unmistakable evidence that they were produced by Jewish people living during the Second Temple period (597 BCE-70 CE), with the entire Tanakh’s translation completed by the second century before Yeshua. Multiple lines of evidence lead in this direction, which is why Septuagint scholars of all backgrounds—that is, both Jewish and Gentile—accept the Jewish origin of the Septuagint, including the Prophets and Writings that were not translated by the original 72. Singer never cites a scholar who agrees with his non-Jewish origin story for the Prophets and Writings because such a scholar does not exist. In this section, we will provide evidence and reasons why. Singer never mentions any of the evidence we will present in this section, namely the evidence provided by Sirach, the Greek Dead Sea Scrolls, pre-Christian Septuagint manuscripts, the date of Esther’s translation, first century Jewish quotations of the Septuagint in the Prophets and Writings, or the reactionary translations of Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus.

The Prologue of The Wisdom of Ben Sira

In the early second century BCE, a Jewish man named Yeshua ben Eleazar ben Sira wrote a book of wisdom sayings (Sirach 50:27). His book has been called various names, including The Wisdom of Ben Sira, Sirach, and Ecclesiasticus. He originally wrote his book in Hebrew, but it was subsequently translated into Greek by the author’s grandson around the year 132 BCE (Sirach, Prologue).[30] The book was included in the apocryphal section in the Greek Septuagint,[31] but its Hebrew form continued to be used in rabbinic circles, as copies of it were found in Hebrew in the Dead Sea Scrolls, at Masada, and in the Cairo Genizah.[32] The sages sometimes quote it approvingly in the Talmud (b. Hagigah 13a; y. Berakhot 11c).

In the prologue to his Greek translation of his grandfather’s work, Ben Sira’s grandson described the difficulties of his task. Attempting to deflect criticism of his work, he conveyed how difficult it was to properly translate the meaning of his grandfather’s Hebrew text into Greek. Although the phrase “the translator is a traitor” would not come into usage for many centuries, the grandson felt the need to declare innocence regarding any inadvertent changes he may have made in his translation.

However, the grandson felt that he was in good company with the many other Jewish translators who had previously translated the Torah, Prophets, and other biblical books into Greek. They, too, had struggled to adequately convey the Hebrew meaning in a Greek form. Here is how the grandson put it:

You are encouraged, therefore, to make a reading with goodwill and care and to have patience for that which we might seem to be incompetent, as to some of the words that were lovingly labored over regarding their interpretation. For the things do not have the same force when expressed in the original Hebrew and when translated into another language. But not only these, but even the law itself and the prophecies and the rest of the books have no small difference when expressed in the original (Sirach Prologue 10–16).[33]

Anyone who has endeavored to translate between two languages can sympathize with the grandson’s plea for patience with his translation’s accuracy. However, for our purposes, his final sentence is the most important. Here, around 132 BCE, we find reference to Greek translations of “the law itself and the prophecies and the rest of the books,” that is, the Tanakh. In other words, by the second century before Yeshua, the entire Hebrew Bible had been translated into Greek. The grandson did not specify who performed the translations, but it would strain the imagination to suppose that Gentiles had performed the job. Jewish people were responsible for these translations, and they were used approvingly by Ben Sira’s grandson, and other Jews as well, although they acknowledged the difficulty of fully conveying the Hebrew meaning through the Greek language.

When considering the origin of the Prophets and the Writings in their Greek translations, Jewish scholars commonly cite this prologue to Sirach. This is true of the Encyclopaedia Judaica (first ed.),[34] the Encyclopedia of Judaism,[35] and the Jewish Encyclopedia.[36] The ease of finding this citation in these commonly used scholarly Jewish reference works calls Tovia Singer’s judgment and trustworthiness into question. In his printed work, Singer never once mentions Sirach’s claims. If he did, he would have to reckon with the evidence it presents against his position.

The Greek Dead Sea Scrolls from the First Century CE

The hard form of Tovia Singer’s argument states that Jews were never involved in translating anything but the Torah into Greek. The Prophets and the Writings, in his analysis, were left in Hebrew until the Christians came along and translated it into Greek for the purpose of forcing Jesus into the Hebrew Bible.

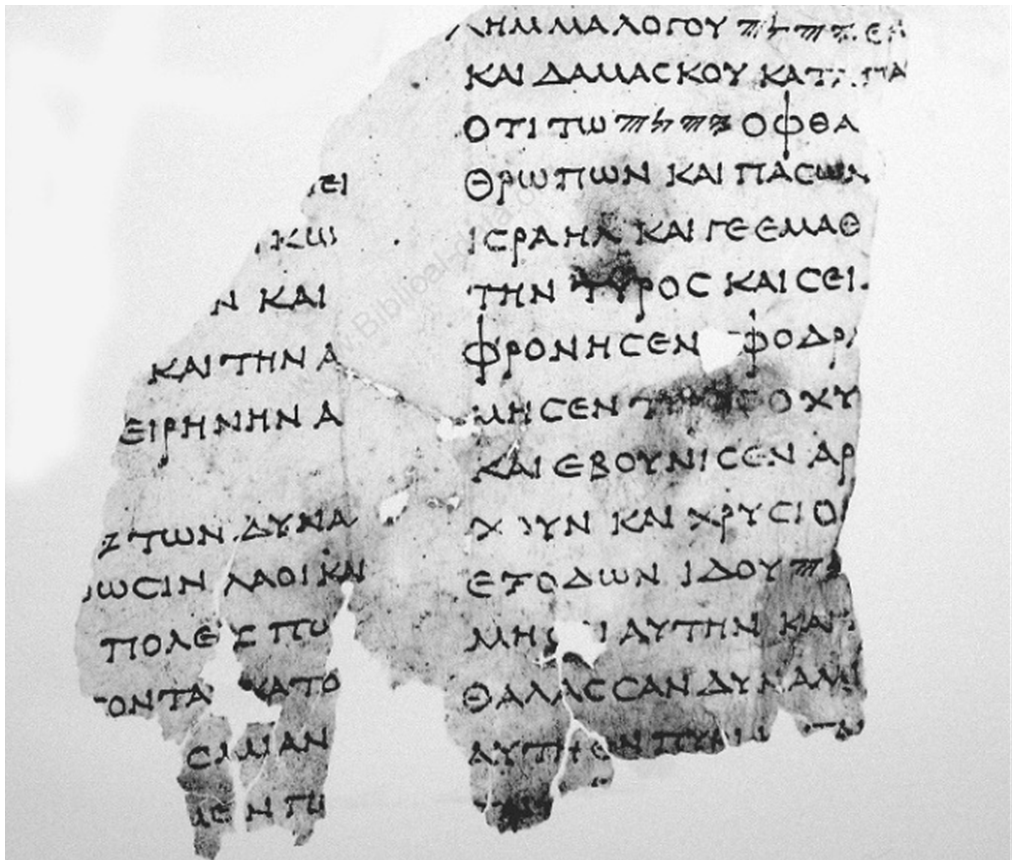

We already saw the emptiness of this argument with Ben Sira. Now, let us consider Greek manuscripts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which show that Jews valued Greek translations in the first century CE. Below is a portion of the scroll called 8HevXII gr, a scroll found in the Nahal Hever cave, dating from the first century CE. The following image, in Greek, includes text from chapters 8 and 9 of Zechariah, that is, one of the twelve minor prophets:

Figure 1 – Greek Minor Prophets Scroll from Nahal Hever (8HevXII gr). Image Source: Wikipedia

This was not the only Greek translation of the Prophets found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In fact, multiple prophets were found in Greek and may be viewed in high resolution at the Israeli Dead Sea Scrolls site.[37] These manuscripts illustrate that even some of the most sectarian and separatist religious groups of Jewish people, the Essenes, living in the Dead Sea region, still saw fit to retain Greek translations of the Scriptures in their libraries. Moreover, it was not just Greek copies of the Torah that they retained; as seen in the scroll above, they retained translations of the Prophets as well.

To summarize, this Greek translation of the Minor Prophets shows that Jewish people were actively translating the Bible into Greek during the Second Temple period. They did not have only the Torah of the 72 elders at their disposal; they translated the Prophets too.

Surviving Greek Manuscripts Dating to Before the Second Century CE

Now that we have been introduced to Greek manuscripts translated by Jewish people that are dated before the Christian era, let us list the other Greek manuscripts of the Prophets and Writings that we have available in the world’s academic institutions today.

Rick Brannan of Logos Bible Software has compiled a database of available Septuagint manuscripts, in consultation with multiple sources of manuscript data.[38] The database includes 2,263 manuscripts at the time of this writing, and they may be searched by date and content, including the ability to search for manuscripts from the first century CE and before that, including the Prophets or the Writings. Searching for manuscripts from the first century CE and earlier is our generously-judged cutoff point for Christian influence, because it is highly unlikely that Christian scribes had any possibility of carrying out a coordinated corruption process during the first century.[39] Tovia Singer, in his more radical claim, would have us believe that there are zero Septuagint manuscripts from the pre-Christian era for the Prophets or the Writings. However, this is not the case. Below is a list of Greek manuscripts that meet the criteria of deriving from a non-Christian source:

| Title | Rahlfs Number | Contents | Century | Online Manuscript |

| 8HevXII gr (Dead Sea Scroll) | 943 | Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Zechariah | 1st CE | Link |

| P. Oxyrhynchus 3522 | 857 | Job | 1st CE | Link |

| P. Oxyrhynchus 5101 | 2227 | Various Psalms | 1st / 2nd CE | Link |

| P. Oxyrhynchus 4443 | 996 | Esther | 1st / 2nd CE | LinkTable 1 – Pre-Second Century CE Greek Manuscripts of Prophets and Writings |

The mere existence of the manuscripts in the table above provides us with evidence that eliminates Singer’s radical claim that only Christians translated the Prophets and the Writings into Greek. Below is another table of manuscripts of Greek translations of the Torah. These manuscripts provide us with pre-Christian versions of the Septuagint with which we can compare later manuscripts and see if the later Septuagint was corrupted, as Singer claims.

| Title | Rahlfs Number | Contents | Century | Online Manuscript |

| Papyrus Fouad 266 | 847, 848, 942 | Deuteronomy | 2nd BCE | Link |

| Papyrus Rylands 458 | 957 | Deuteronomy | 2nd BCE | Link |

| 4Q119 | 801 | Leviticus | 2nd BCE | Link |

| 4Q120 | 802 | Leviticus | 1st BCE | Link |

| 4Q121 | 803 | Numbers | 1st CE | Link |

| 4Q122 | 819 | Deuteronomy | 2nd BCE | LinkTable 2 – Pre-Second Century CE Greek Manuscripts of the Torah |

Singer would have his audience believe that the only surviving manuscripts of the Septuagint are those produced by Christians. However, as the tables above illustrate, Singer has misled his audience because there are several pre-Christian manuscripts of the Septuagint available today for the Torah, Prophets, and Writings. Although the best and most complete manuscripts of the Septuagint came from Christian scribes centuries later, we are not dependent upon those later Christian scribes to determine that translations of the Writings and Prophets featured in the Septuagint was produced by Jewish people and used by them for centuries.

The Date of the Septuagint Translation for Esther

At the end of the Septuagint version of Esther, there is a postscript, called a colophon, which gives valuable information that proves that Jews translated the Writings into Greek and that the Septuagint was not produced by Christians. The colophon reads,

In the fourth year, while Ptolemais and Cleopatra were reigning, Dositheos, who said he was a priest and Levite, and Ptolemy, his son, brought in to Egypt the preceding letter concerning Purim, which they said was authentic and had been translated by Lysimachus, the son of Ptolemais, one of the residents in Jerusalem.[40]

Commenting on this passage, the Lexham Bible Dictionary states, “This verse provides a date to the text (it was known by 114 bc or 78 bc depending on which Ptolemy is referred to), the name of the translator (Lysimachus), and a place of translation (Jerusalem).”[41]

Albert Baumgarten, the author of the entry on Esther in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, opted for the later of the two dates in his analysis:

Esther was translated into Greek by Lysimachus son of Ptolemy of Jerusalem. His translation was brought to Egypt in the “fourth year of the reign of Ptolemy and Cleopatra,” according to the colophon at the end of the Greek version. Of the three Ptolemies associated with a Cleopatra in the fourth year of their reign, the most probable one in this case is Ptolemy XII Auletos and his sister and wife Cleopatra V. Documents about Ptolemy XII and Cleopatra V are the only ones which illustrate in the same royal style as the colophon. The translation was thus brought to Egypt in the year 78/77 B.C.E.[42]

Thus, the Septuagint version of Esther that is in common use today was translated by a Jewish resident of Jerusalem, likely in the early first century BCE. Because Esther is part of the Writings, this claim also serves to disqualify Tovia Singer’s claim that the Writings were not translated by Jews into Greek, and that the Septuagint version we have today was produced by Christians.

First Century Jewish Uses of the Septuagint: Josephus and Philo

The first-century CE Jewish historian Josephus was intimately familiar with the entire Septuagint that we have today. In his voluminous works, including a paraphrase of the entire Hebrew Bible, he did not just quote the Torah when citing the Greek translation of Scripture. He cited the Prophets and the Writings as well, and his quotations usually match the Septuagint after the book of Judges. Second Temple Judaism scholar Martin Hengel said that Josephus tended to use the Hebrew Bible as the source of his citations from Genesis to Joshua/Judges, but more frequently cited the Septuagint from the books of Samuel forward.[43]

In his study on Josephus’s quotations of the books of Samuel, Eugene Ulrich writes, “Josephus agrees in general with the [Qumran, Septuagint, C] tradition rather than the [Masoretic Text, Targum, Theodotion] tradition…. The results demonstrate that Josephus shows no dependence on [the Masoretic Text] specifically.”[44] Likewise, Josephus knew the Septuagint version of Daniel, which he cited frequently in his discussions about prophecy.[45] Thus, the works of Josephus illustrate that the Septuagint version of the Prophets and the Writings were commonly in use in Jewish circles in the first century CE.

The first-century Jewish philosopher Philo, who knew little to no Hebrew, quoted the Greek version of the Scriptures throughout his works. This included quotations of 1 Samuel, 1 Kings, 1 Chronicles, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Hosea, Jonah, and Zechariah.[46] In some places, his quotations are verbatim from the Septuagint,[47] and in other places Philo has minor differences that amount to the same meaning.[48]

As an example of a minor update from the Septuagint, in On Dreams 2.26, Philo quotes from Isaiah 5:7, saying, “The vineyard of the Lord Almighty is the house of Israel.”[49] In the Septuagint, the translator opted to keep the Hebrew word for “Almighty,” merely transliterating it as σαβαωθ, “sabaoth.” When Philo cited the translation, he updated it with a Greek word that contained the same meaning: παντοκράτορος, pantokratoros. Thus Philo shows his dependence on the Septuagint for the Prophets and Writings, but felt free to update it for the purpose of clarity.

The first-century Jewish authors Josephus and Philo had the Septuagint at their disposal when they wrote their works. They cited the Septuagint for both the Prophets and the Writings. The same is true for the Jewish authors of the New Testament, who were contemporaries of Josephus and Philo.

Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus, and the Implied Earlier Existence of the Septuagint

By the second century CE, the Septuagint had been the widely accepted translation of the Bible for Jewish people for centuries, including the Jews who believed in Jesus. When these Jewish believers started appealing to the Septuagint to explain their faith in Jesus, some Jewish religious leaders sought to distance themselves from the popular Septuagint translation because they rejected Yeshua’s messiahship. They embarked on this separation by commissioning a proselyte named Aquila to produce a new Greek translation (y. Megillah 71c). This translation attempted to be extremely literal to the Hebrew text and to retranslate passages that the New Testament appealed to for Messianic evidence (like Isaiah 7:14).[50] Aquila’s literal translation was so dependent upon prior Hebrew knowledge that it was almost unreadable by anyone lacking such background.[51]

After Aquila, two other Jewish translators sought to retranslate the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek: Theodotion, in the middle of the second century, and Symmachus, at the end of the second century. Although we do not have full manuscripts of these three second-century Jewish translators available today, ironically, Christian scribes, starting with Origen’s Hexapla in the third century, preserved many of their readings in marginal notes and commentaries. Frederick Field compiled these renderings in his edition of the Hexapla, which continues to be the standard edition, despite its 1875 date of publication.[52] Thus, despite not having any complete manuscripts from Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus today, we still have many examples of their translations available.

There are several ways these three Jewish translators challenge Rabbi Singer’s claims about the Septuagint. First, we have many preserved readings of the three translators available for the Prophets and the Writings. For example, we can see that all three, writing in a post-Yeshua context full of controversy, opted to translate Isaiah 7:14 as νεανις (neanis, “young woman”) rather than the Septuagint’s παρθενος (parthenos, “virgin”).[53] Whereas Jews before Yeshua may have been open to the passage speaking about a virgin, after Yeshua’s coming this translation became too inconvenient for Jewish authorities who rejected his messiahship, and their opinion consolidated around “young woman,” where it remains today. Many other passages in the Prophets and Writings may be consulted in Frederick Field’s compilation. Thus, these three translators undermine Singer’s contention that Jews never translated the Prophets and the Writings—for at least these three did.

Second, these three undermine Singer’s claims of Christian conspiracy. Although these three translations were produced by Jewish communal leaders in direct competition with the rising claims of Yeshua-followers, the Jewish community did not preserve the translations of Aquila, Theodotion, or Symmachus. It was Christian scribes and scholars who preserved these readings, even when their readings caused controversy for Christians. If Christians were conspiring to create their own translations and hide all previous Jewish translations that went against their theology, why would they preserve these three Jewish translations of the second century CE?

Third, these three translations presuppose a preexisting Septuagint translation since they sought to do away with the previous Greek translation. The reason the three translations were needed, in second-century Jewish minds, was to combat the growing Christian use of the Septuagint. Why be dependent upon the same translation as one’s adversaries? Thus the very existence of these translations illustrate that a pre-Christian Greek translation had been used widely in Judaism, yet for apologetic purposes it needed to be phased out.

Fourth, Theodotion exemplifies how Christian scribes were not slavish in their devotion to the Septuagint. According to many church fathers, the Septuagint translation of Daniel was deficient. This judgment is justified, as the Septuagint of Daniel was disorganized and loose with its translation of the Hebrew and Aramaic text. In response, at an early period, Christians discarded the Septuagint version and adopted Theodotion’s translation of Daniel as their official version of Daniel in the third century.[54] This openness to accept the Septuagint at times, and not at others, is reflected in the New Testament itself, where sometimes the authors quoted the Tanakh in a way that better reflected the proto-Masoretic Hebrew, rather than the Septuagint.

Finally, we must note that Singer never mentions the existence of Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus in his written work.[55] Either he is unaware of their existence, which points to irresponsible neglect of research, or he knows of their existence and is choosing not to mention them. Any retelling of the Tanakh’s relationship with Greek translation needs to include the three second-century translators, for their translations and history are woven together into the story of the Septuagint as we know it today.

Jewish People Translated the Prophets and the Writings Before Yeshua’s Time

After surveying a wide range of sources regarding the origins of the Greek translations of the Prophets and the Writings, we have found conclusive evidence that they were produced by Jewish translators before the time of Yeshua. These Greek translations found widespread acceptance and usage in Jewish communities throughout the land of Israel and the diaspora. One can only deny these things if one chooses not to investigate the historical evidence.

In his printed work, Rabbi Singer never addresses any of the categories of evidence we have presented so far.[56] He never mentions the prologue of Ben Sira, nor does he cite any ancient Septuagint manuscripts, nor does he consider the postscript of Esther or the inclusion of Septuagint quotations in ancient Jewish works. He shows no indication that he has read an article in any of the three major Jewish encyclopedias on the Septuagint, each of which give reason to deny his theory. His omissions are fundamental, irresponsible, and should not be ignored by anyone considering his handling of these matters.

Did Christians Corrupt the Greek Translations After Yeshua’s Time?

Historical evidence conclusively illustrates the Jewish origin of the Septuagint, including the Torah (translated by the 72) and the Prophets and the Writings (which were translated by other Jewish translators). The evidence in this regard is overwhelming—which does not speak well of Singer’s desire to devise a plausible argument regarding the Septuagint. However, his claims about the Septuagint have not yet been fully refuted.

A second major claim Singer makes is that Christians were responsible for corrupting the Prophets and the Writings into the Septuagint manuscripts we have today. With this second argument, he does not need to accurately identify the original translators of the Prophets and the Writings because the original work has been lost. All we have today, supposedly, are the tampered and corrupted documents handed down to us through the church, which he implies is dishonest.

We have already seen that a major premise here is false; we do have Greek manuscripts and quotations of the Septuagint from Jewish sources that have been untouched by Christian influence. The Greek Minor Prophets scroll in the Dead Sea Scrolls is a prime example, but not the only one. However, our pre-Christian manuscripts for the Septuagint are incomplete and do not come close to the quality and preservation of the ones produced by professional Christian scribes in later centuries, such as Vaticanus and Alexandrinus. As Septuagint scholar S.K. Soderlund summarizes,

The chief codices of the Greek OT are also the most important of the Greek NT: Vaticanus (B) and Sinaiticus, both 4th cent. a.d., and Alexandrinus (A), 5th century. Of these three, B has been confirmed as containing the best text, with certain notable exceptions, e.g., Judges and Isaiah. In the 20th cent., however, numerous papyri have been discovered; some are from the 1st and 2nd cents b.c. and thus antedate the chief uncials and the Christian “takeover” of the LXX.[57]

The “takeover” mentioned here is a reference to the rise of professional Christian scribes in the fourth century who produced the best manuscripts of the Septuagint that remain available today (Vaticanus, Sinaiticus, and Alexandrinus). However, as Soderlund mentions, we have examples of the text before Christian scribes ever got their hands on the Septuagint. Such pre-Christian manuscripts would have been free of any supposed Christian corruption influence.

Even so, Singer does not cite any before-and-after examples of corruption except one: the Talmudic discussion in Megillah 9a–b. For some reason, Singer has decided to omit all modern scholarship, all manuscript evidence, and all historical investigation in favor of a rabbinic passage dating to the fourth century CE.[58] While this preference for highlighting a late talmudic discussion may be plausible for his Orthodox Jewish audience, it should not be at the expense of other significant (and earlier) evidence on the matter. In any case, the talmudic passage cites fifteen places where the translation of the 72 elders differed from the Hebrew original. Singer summarizes:

Of these 15 phrases which appeared in the original Septuagint (Genesis 1:1; 1:26; 2:2; 5:2; 11:7; 18:12; 49:6; Exodus 4:20; 12:40; 24:5; 24:11; Leviticus 11:6; Numbers 16:15; Deuteronomy 4:19; 17:3), only Genesis 2:2 and Exodus 12:40 are found in the current Septuagint.[59]

Based on this, he reasons, “Of these 15 unique translations, only two are extant. It’s clear that the Septuagint’s version of the Torah is a corruption of the original translation made by the 72 Jewish scribes.”[60] This is the only tangible reason Singer gives for distrusting the Septuagint version of the Torah in our manuscript tradition; for the Prophets and the Writings, he proclaims their non-Jewishness, which we have already disproven. Thus, our rebuttal of Singer requires that we address this passage he has cited from the Talmud to see if Singer’s claims of conspiracy have any plausibility.

We will investigate the Talmud passage thoroughly below, however, no Septuagint scholars think that Singer’s claims of conspiracy have any plausibility, and neither do we.

Only Singer Supports Conspiracy Theories About the Septuagint Corruption

In this article, we have reviewed a wide variety of published scholars regarding their findings, theories, and arguments about the Septuagint’s origins, complexities, and transmission. The bibliography at the end of this article includes multiple monographs on the Septuagint, entries on the Septuagint in three major Jewish encyclopedias, entries from Christian encyclopedias, and essays by credentialed Jewish and Christian authors. None of them accuse Christians or Christianity of corrupting the Septuagint. On this matter, Rabbi Tovia Singer is alone.

Few scholars even hint at the possibility that there could have been a Christian corruption. For example, when summarizing scholarly views on the origin of the Septuagint (including the Prophets and the Writings), a recent introduction to the Septuagint does not mention Christian corruptions or fabrications.[61] In Leonard Greenspoon’s article in Encyclopaedia Judaica, intended for Jewish audiences, he makes clear that there is no reason to think that there was intentional Christian corruption:

There is no reason to think that Christian scribes deliberately changed the originally Jewish text for tendentious, theological reasons, although it is certain that all sorts of scribal changes led to many differences, some substantial, between what the codices contain and what the earliest Greek (or Old Greek) read. We are not without earlier evidence in the form of a limited number of Greek texts from Qumran and other Dead Sea locales; citations, allusions, and reworkings in the New Testament; and Qumran scrolls that preserve in Hebrew the likely Vorlage or text that lay before the LXX translators.[62]

Scholars who have made Septuagint studies the focus of their career, including Jewish ones, see no evidence of Christian conspiracy. The burden of proof is on Rabbi Singer to justify his accusations of Christian corruption.

Singer’s Supposed Talmudic Evidence of Christian Corruption in Megillah 9a–b

Singer believes that he has provided evidence of Christian corruption of the Septuagint through his appeal to a Talmudic passage on the Greek translation of the Scriptures.[63] In order to properly evaluate Singer’s use of the Talmud in his argument, it would be wise to review the Talmudic passage in full, presented below in Jacob Neusner’s translation:

As is taught: An episode about Ptolemy, who gathered 72 elders and cloistered them in seventy-two buildings, and did not tell them why he had gathered them: He entered to [speak with] each and every one and said to them: Write for me the Torah of Moses your master. The Holy One, Blessed Be He, advised each and every one of them, and they all agreed to one position [on a number of problematic passages], and they wrote for him:

According to Singer, these rabbinic citations of the translation of the 72 are proof that the Septuagint we have today has been corrupted. Is this true?

The Difficulty of Assessing Singer’s Claim

The section of the Talmud we just quoted in English was originally written in Hebrew.[65] However, the rabbis’ quotations themselves are supposed to be reflective of what the Greek said, and the Greek is supposedly different than the original Hebrew. Thus, no one can properly assess the sages’ claims without knowing both languages, or citing scholars who do. In addition, to handle this subject correctly, one needs to know how to propose Greek-Hebrew equivalents, must know the principles of textual criticism, and must have access to the manuscript evidence of the Septuagint and its many derivatives. In short, this is an advanced topic requiring advanced skills.

Rabbi Tovia Singer is not a Septuagint scholar and does not show evidence of having the advanced skills necessary to give an informed opinion about the sages’ claims. Although I have training in each of these advanced subjects, I do not claim to be an authority on these matters. In order to justify my own opinions on this subject, my confidence in my own skills is limited. To fill in the gaps of my knowledge and experience, I rely on credentialed, respected scholars in the field of the Septuagint, and if I can find a Jewish scholar in that area, that is even better.

Thus, it is extremely helpful that a Jewish Septuagint scholar of the caliber of Emanuel Tov has published an extensive analysis of the sages’ quotations in Megillah 9a–b, and other Jewish scholars, like Lawrence Schiffman, have chimed in.[66] Although I will be providing an original analysis of each of the fifteen rabbinic quotations below, I must stress that my conclusions here are not my own, but are in agreement with Jewish Septuagint scholars who have far more credibility on these matters.

Advanced Analysis: Megillah 9a–b and the Septuagint

In the tables below, each of the fifteen statements are assessed upon whether the Talmud’s quotation is present in our current Septuagint manuscripts, and whether our current Septuagint (LXX) manuscripts agree with the Masoretic Text (Hebrew). We will note any discrepancies or agreements as well. Readers who are confused about the complexity of this study are encouraged to skip to the end of this section. In short, we will find that Rabbi Singer’s handling of this passage, and its implications for the Septuagint, are without merit.

Table 3 – Talmud Statements 1–3

|

Statement No. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

[67]Talmud’s LXX in English |

“God created in the beginning” (Gen 1:1). |

“I will make man in a form and likeness” (Gen 1:26). |

“And He finished on the sixth day… and He rested on the seventh day” (Gen 2:2). |

|

Nature of Supposed Difference |

Word order |

Missing plurals “let us make” and “our” |

Makes God finish on sixth day |

|

Talmud’s LXX Reflected in LXX Manuscripts? |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Do LXX Manuscripts Agree with Hebrew? |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Sources that Agree with Talmud |

— |

— |

LXX |

|

Sources that Agree with LXX Manuscripts |

Philo (On Creation 7), Symmachus, Theodotion; Aquila agrees with order but has “In the head [of time] God formed”; allusion in John 1:1 |

Philo (On Creation 24, Confusion 169); Hellenistic Synagogal Prayers 3.19 and 12.36; 1 Clement 33:5; Barnabas 5:5; Justin Dialogue 62 |

Samaritan Pentateuch[68] |

|

Century of Earliest LXX Support |

First CE (Philo, John) |

First CE (Philo) |

— |

Analysis Notes, statements 1–3:

Table 4 – Talmud Statements 4–6

|

Statement No. |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

[70]Talmud’s LXX in English |

“Male and female He created him” (Gen 1:27 or 5:2). |

“I will go down, and I will confuse their speech” (Gen 11:7). |

“And Sarah laughed among her relatives” (Gen 18:12). |

|

Nature of Supposed Difference |

“Him” instead of “them” |

Singular “I” instead of “we” |

Addition of “relatives” |

|

Talmud’s LXX Reflected in LXX Manuscripts? |

No |

No |

No |

|

Do LXX Manuscripts Agree with Hebrew? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Sources that Agree with Talmud |

— |

— |

— |

|

Sources that Agree with LXX Manuscripts |

Sirach 17:3; Jubilees 2:14; Philo (Heir of Divine Things 33); Matthew 19:4; Mark 10:6; Aquila, Theodotion, Symmachus, 1 Clement 33:5 |

Philo (Confusion 37, 168, 182); Recognitions of Clement 2.39; Aquila has similar plural verb |

— |

|

Century of Earliest LXX Support |

Second BCE (Sirach, Jubilees) |

First CE (Philo) |

— |

Analysis Notes, statements 4–6:

Table 5 – Talmud Statements 7–9

|

Statement No. |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

[72]Talmud’s LXX in English |

“For in their anger they slew an ox, and they willfully hamstrung a bull” (Gen 49:6). |

“And Moses took his wife and his children, and he mounted them on a people-carrier” (Exod 4:20). |

“And the length of time that the Israelites dwelled in Egypt and in other lands was 400 years” (Exod 12:40). |

|

Nature of Supposed Difference |

“ox” instead of “men” |

“people-carrier” instead of “donkey” |

Addition of “and in other lands” |

|

Talmud’s LXX Reflected in LXX Manuscripts? |

No |

Likely |

Partially |

|

Do LXX Manuscripts Agree with Hebrew? |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Sources that Agree with Talmud |

— |

— |

Partially LXX |

|

Sources that Agree with LXX Manuscripts |

Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus 1.7 |

— |

Samaritan Pentateuch |

|

Century of Earliest LXX Support |

Second-Third CE |

— |

— |

Analysis Notes, statements 7–10:

Table 6 – Talmud Statements 10–12

|

Statement No. |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|

[74]Talmud’s LXX in English |

“And he sent the Israelite youth” (Exod 24:5). |

“And, against the Israelite youth, he did not extend his hand” (Exod 24:11). |

“Not one precious thing of theirs did I take” (Num 16:15). |

|

Nature of Supposed Difference |

“youth” or “elect” |

“youth” or “elect” |

“precious thing” instead of “donkey” |

|

Talmud’s LXX Reflected in LXX Manuscripts? |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Do LXX Manuscripts Agree with Hebrew? |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Sources that Agree with Talmud |

LXX |

— |

LXX |

|

Sources that Agree with LXX Manuscripts |

— |

Philo, Confusion 56 |

Philo, Confusion 50, Irenaeus, Against Heresies 4.26.4 |

|

Century of Earliest LXX Support |

— |

First CE |

First CE |

Analysis Notes, statements 10–12:

Table 7 – Talmud Statements 13–15

|

Statement No. |

13 |

14 |

15 |

|

[77]Talmud’s LXX in English |

“That the Lord your God distributed them to enlighten all of the nations” (Deut 4:19). |

“And he went and worshipped other gods, which I have not commanded to worship” (Deut 17:3). |

“And they wrote for him “the short-legged one” (Lev 11:6), and they did not write for him “the hare” (arnevet), because the wife of Ptolemy is named Arnevet, in order that he not say: The Jews have made a joke of me and put my wife’s name in the Torah.” |

|

Nature of Supposed Difference |

“to enlighten” instead of “allotted / apportioned / divided” |

Addition of “to worship” |

“the short-legged one” instead of “the hare” |

|

Talmud’s LXX Reflected in LXX Manuscripts? |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Do LXX Manuscripts Agree with Hebrew? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Sources that Agree with Talmud |

— |

— |

— |

|

Sources that Agree with LXX Manuscripts |

Origen, Contra Celsus 5.6, Eusebius, Demonstration 4.8 |

— |

LXX Deut 14:7 |

|

Century of Earliest LXX Support |

Third CE (Origen) |

— |

— |

Analysis Notes, statements 13–15:

Summary of Findings in the Talmud

In our investigation of the fifteen passages, we have found the Talmud’s report to be an outlier that cannot be accounted for in the manuscript evidence. The Talmud is describing a Greek translation that we have no manuscript evidence for. Orthodox Jewish scholar Lawrence Schiffman comments on the Talmud’s claims in Megillah and concludes, “Scholarly investigation of these variants shows that the account reflects no actual familiarity with the Septuagint, which, like the rest of Greek Jewish literature, was apparently lost to the rabbinic Jewish community.”[80] My assessment presented here aligns with the summary of Emanuel Tov:

A comparison of the passages with the LXX shows that nine passages in the list differ from the LXX, while five agree with it (3, 8, 10, 12, 15), with one passage being close (9).[81]

Tov concludes that five of the passages agree with the Septuagint, in line with our investigation, and disagreeing with Singer, who said that only two agreed.[82]

After assessing each of the fifteen instances, we have come to the following conclusions:

Based on these findings, we are now prepared to critically assess and refute Tovia Singer’s argument concerning the purported evidence of the Septuagint’s corruption.

A Refutation of Singer’s Argument Regarding Megillah 9a–b

Considering the investigation above, it will now be demonstrated that Tovia Singer’s skepticism about the integrity of the Septuagint lacks merit. The evidence he points to in the Talmud does not support his conclusion, but rather, ironically, leads in the opposite direction.

First, if the sages were right that the original Septuagint translation included these fifteen differences, and Christians later changed them, why did Christians pick these fifteen verses to change? Several of the changes relate to donkeys, rabbits, and oxen! Only a few of them have any kind of theological importance, and it is unclear what Christian motive there could have been for those. If Christians wanted to corrupt the Torah, could they not have found more substantial passages to change?

Second, we have seen that Tovia Singer is unable to reliably report the number of agreements between the Talmud and the LXX manuscripts (3, 8, 10, 12, 15 in full, and 9 partially). These six instances correctly report what the LXX of the Torah says, but Singer claims that only two agree (3, 9). Additionally, he is imprecise in that he neglects to mention that 9 only partially agrees. These omissions should lead us to question Singer’s scholarship on this matter.

Third, the Talmudic sages themselves were often confused about the Greek that was before them and reported differences that were not actually differences (8, 10, 11, 15). When Singer appeals to the authority of the sages to report these differences, he inherits their mistakes and bases his skepticism upon false foundations.

Fourth, in seven of the instances, we were able to confirm the Septuagint’s wording in other ancient works, against the wording of the Talmud. Five of these instances pre-date the rise of Christianity, thereby illustrating the Septuagint’s stability before any supposed Christian corruption.

Fifth, in places where the Talmud differs from the Septuagint manuscripts available today (twelve instances), we were unable to find any ancient sources that agreed with the Talmud’s rendering. The sages’ reporting is unverifiable and isolated. If one fully trusts the sages of the Talmud as accurate reporters, then one may not be bothered about their isolated reporting, and Singer appears to be in this camp. We have illustrated that the sages were not always reliable in their handling of the translation differences and there are many sources that contradict what they say. Singer’s uncritical appeal to the Talmud’s reporting on the matter is unwise.

Sixth, and most importantly, Tovia Singer’s argument self-destructs in a way he did not anticipate. Singer wants his audience to believe that Christians were responsible for corrupting the Septuagint. Supposedly, the version reported by the rabbis was the original Septuagint, and the Septuagint manuscripts we have today were all doctored by Christians. Singer appeals to the sages’ fifteen examples as representative evidence of the corruption. Ironically, out of the fifteen supposed corruptions, the Septuagint manuscripts we have today agree with the Masoretic Hebrew in twelve of the cases. If, hypothetically, Christians were responsible for the differences after the Talmud’s version, then they should be called “corrections,” not “corruptions.” The rabbis’ supposed Septuagint differed from the Hebrew in all fifteen instances, but the Septuagint that survived agreed with the Hebrew in twelve out of the fifteen. In other words, it was the sages’ translation that was corrupt, rather than the one used in Christian circles. The result of Tovia Singer’s odd logic would lead to less trust in the Septuagint manuscripts that we have today because they agree more with the Hebrew.

In sum, Singer’s analysis of the Septuagint as reported in Megillah 9a–b is misleading and without merit. This was the only tangible, verifiable argument he made in favor of the Septuagint’s corruption by Christians, and the argument is baseless. There is no evidence that Christians corrupted the Greek text of the Torah, the Prophets, or the Writings.

Brief Responses to Singer’s Claims

Near the beginning of this article, we provided Tovia Singer’s assertions in his own words, and then we summarized his views into eleven points. We assessed Singer’s claims by asking two broad questions:

Now that we have answered these questions by looking at the historical record, we are now prepared to respond to each of Singer’s eleven points.

Partially true. Singer illustrates his pro-Talmudic bias by portraying the 72 translators as “rabbis.” In the third century BCE, this term was not yet used in the now-common connotation of Torah scholar and teacher. The title “Rabbi” as an occupation did not come into common use until the first century CE,[84] with Jesus as one of the earliest on record to be described with the title (Matt 26:25; Mark 9:5; John 1:38). The earliest report of the Septuagint’s translation, The Letter of Aristeas, calls the 72 translators “elders” (πρεσβυτέρους, Aristeas 39, 46, 310), six per Israelite tribe. A true statement would be to say that the early reports say that the Greek translation was performed by 72 Jewish elders.

Correct. The original translation project by the 72 elders was limited to translating the Torah alone. The ancient sources are unanimous in this respect.

False. Words change in meaning over time and with usage in living communities. The term “Septuagint” was expanded to refer to all the old Greek translations of the entire Tanakh, even those that were not translated by the 72. This imprecise expansion, for better or worse, has become the standard usage.

False. The Talmud’s reporting on this matter is questionable, as it is often confused and does not reflect any existing manuscripts or quotations in ancient works. Moreover, Singer incorrectly reports the number of instances where the Talmud preserves an accurate knowledge of the Septuagint.

False. At best, Singer’s argument could only prove fifteen instances (out of the entire Torah) where there have been corruptions, far less than “almost entirely a complete corruption.” However, Singer’s analysis fails to substantiate even those fifteen. On the contrary, the Septuagint that we have today has been consistently shown to be reflective of the Septuagint that was in use by Jewish people during the Second Temple period. Jews ceased using the Septuagint because of the Christians’ use of it in religious disputes, not because of the Septuagint’s corruption.

False. Textual and manuscript evidence proves otherwise. Against Singer’s position we have evidence from Sirach, the Dead Sea Scrolls, other ancient scrolls, the Septuagint of Esther, Jewish quotations of the Prophets and Writings in the first century, and the story behind the three second century translators, Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus.

False. Singer provides no positive evidence of this claim besides his speculative and mistaken handling of Megillah 9a–b. We have much evidence that the Prophets and Writings were preserved in their Greek translations.

False until proven true. Singer provides no evidence for this speculation. On the contrary, Jews wrote the New Testament within a Jewish context, using Jewish sources and Jewish ways of thinking, and the use of the Septuagint was part of that Jewish mode of thinking.

False. The old Greek translations of the Prophets and Writings, now known as the Septuagint, were all translated by Jews and were put into use in Jewish communities for centuries. The Christian church inherited these translations and preserved them intact, as comparisons with ancient Jewish quotations illustrate.

False. The Septuagint is a Jewish work, and any doubt cast upon the Septuagint’s translation must be performed on a verse-by-verse, word-by-word basis. The work as a whole cannot be dismissed as a Christian production or conspiracy.

False. While the most complete and reliable Septuagint manuscripts that survive today were copied by Christian scribes in the fourth century and later, these are not the only Septuagint manuscripts available today. We have manuscripts of the Septuagint that pre-date the rise of Christianity and they can be checked against the Christian manuscripts. Jewish scholars who do such comparisons see no grounds for charging Christian scribes with charges of conspiracy and corruption.

An Unsaid Bias: Rabbi Singer and Maimonidean Orthodoxy

While accusing ancient Christians and Christianity in general of malevolent bias, Singer unfortunately neglects to instruct his readers about his own biases and presuppositions. Rabbi Tovia Singer, as an Orthodox rabbi, cannot allow himself to affirm the accuracy of the Septuagint because he is constrained from doing so by his own theological commitments. In other words, no matter what evidence may favor the Septuagint’s wording over the Hebrew manuscript tradition, he can never allow himself to consider the evidence, because by doing so, he would be calling the majority position of Orthodox Judaism into question. He might pay a personal price too; he may be criticized by many Orthodox Jews if he were to lend credibility to the Septuagint.[85]

Why? Because of Orthodoxy’s commitment to Rambam’s (Maimonides’s) eighth principle, which states,

The eighth fundamental principle is that the Torah is from heaven, that we should believe that the entire Torah that we possess today is the Torah that was given to Moses, and that it is of Godly origin in its entirety.[86]

והיסוד השמיני הוא – תורה מן השמים. והוא, שנאמין שכל התורה הזו הנמצאת בידינו היום הזה היא התורה שניתנה למשה, ושהיא כולה מפי הגבורה[87]

According to Orthodox Jewish thought, the written Torah is a holy, perfect, and godly book in the form that we have it today. Not only was the Torah given to Moses supernaturally at Sinai, but it has also been preserved supernaturally until today, right down to the very letter. This principle of faith is not negotiable, according to Rambam’s eighth principle. Thus, a person upholding the eighth principle should never allow any other version of the Scriptures—such as the Septuagint or the Dead Sea Scrolls or any other source—to revise or correct any text in the Hebrew manuscript tradition. Modern Orthodox Rabbi Josh Yuter discusses the implications of such a position for Orthodox Jews:

The crucial words in Maimonides’ formulation is that the Torah “הנמצאת בידינו” – that we currently possess in our hands – is what God dictated to Moses…. As written, Maimonides’ formulation does not allow for any textual variants since whatever text we have must have been exactly what was transmitted to Moses at Sinai… [O]nce we concede any textual variant in the Torah, Maimonides’ 8th principle is no longer valid.[88]

Yuter is one of the few voices within Orthodoxy, along with Marc B. Shapiro,[89] who have called for a revision to the standard Orthodox position on these matters so errors in the manuscript copying process may be repaired.

At Chosen People Answers, we affirm the authority and divine origin of the Hebrew Scriptures. Moses indeed received the Torah from Hashem at Sinai, and the Nevi’im and Ketuvim are from Heaven as well. However, considering the evidence provided by many biblical manuscripts, we cannot follow the Orthodox Jewish position that there are no errors in the textual transmission of the Torah. One can easily demonstrate that there are indeed differences in the Hebrew textual tradition of the written Torah—that is, the manuscripts that we have today have significant errors in certain locations.[90] Moreover, there are more accurate readings to be found in those passages in the Septuagint, Dead Sea Scrolls, and other textual traditions. To accurately follow the inspired words of Moses and the prophets, a biblical scholar needs tools to identify which verses and words have been corrupted over time in the manuscript copying process. This is the science of textual criticism, and it does not challenge our faith in the God of Israel, but actually strengthens it.

Singer, however, is constrained to affirming the Masoretic family of manuscripts, with their inconsistencies and copyist mistakes included. Because of his adherence to Orthodoxy, which requires an affirmation of the Masoretic textual tradition only, Singer cannot allow himself to consider the value of the Septuagint (or any other textual source, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls) to fix copyist mistakes in the Masoretic manuscripts.

This unspoken bias may explain why Singer sees little need to support his argument with tangible historical evidence. His rejection of the Septuagint does not need evidence. He already has his theological precommitments, derived from Maimonides, in agreement with his community, and he has developed a conspiracy theory to justify himself in light of the Septuagint’s existence.

However, once we look at the full range of historical evidence available to us—and not just the narrow range of facts cited by Singer—we can see that his argument is a speculative attack on the New Testament that is pragmatically useful for Singer, but is historically false.

The One Point Singer Has in His Favor

Given the preceding arguments, Tovia Singer’s position on the Septuagint’s origin ought to be ignored. His arguments have no merit and are disproven by the historical evidence. Singer’s argument is constructed for the polemical purpose of undermining any attempt to appeal to Septuagint translations of prophecies, such as Isaiah 7:14 and Psalm 22:16. He is eager to dismiss the entire Septuagint—a production by his ancient Jewish brothers and once read by millions of Jews—for the benefit of pragmatic argumentative points against contemporary Messianic Jews and Christians. We have demonstrated the hollow nature of his claims.

Despite all of this, Singer could conceivably retreat from his positions and still have one last point to make regarding the Christian conspiracy charge. It is based on this inconvenient truth: We do not have any pre-Christian manuscript or quotation evidence available for the Greek translations of controversial passages such as Isaiah 7:14 or Psalm 22:16. Neither Philo, nor Josephus, nor any other Jewish writer who wrote in Greek provides us with evidence regarding what these verses said in the first century CE and prior. All we have regarding these particular verses is what the later Christian-copied manuscripts of the Septuagint say, as well as the text of the New Testament itself (which was written by Jews).

In light of this, Singer could conceivably reply, “Ok, I was wrong about the Septuagint being translated and edited by Christians. It was translated by Jews, even the Prophets and the Writings. But in the case of parthenos (Isa 7:14) and the like, those words were corrupted by Christians.” If he were to make this more limited claim, there would be no evidence outside of Christian-produced manuscripts that we could appeal to prove or disprove it. Thus, we have here an argument from silence that cannot be disproven.

If Singer were to say such a thing, there would be nothing anyone could say against it, except this: “How could one know, Rabbi Singer, that those words were corrupted? What positive evidence can you provide? A claim with no evidence in its favor is mere speculation and ought not be given any acceptance.”

At best, Singer has an argument from silence in his favor. He could exploit this to sow doubt because it is not falsifiable. But why should such an argument be trusted? He has been shown to engage in misleading half-truths and extensive misinformation in relation to the Septuagint. There are many other, more educated, more sophisticated, and more reliable Jewish authorities concerning the Septuagint than Rabbi Tovia Singer.

We admit that there is no ancient manuscript evidence of the original Greek wording of prophecies such as Isaiah 7:14, besides that provided in the Septuagint text tradition, which was preserved by Christian scribes. Thus, each person must choose to weigh the options and make a decision of trust. Are Yeshua’s words and message trustworthy? Is the New Testament God’s gift to Israel and the nations for their healing, atonement, and new life? If so, questions about the Septuagint should not dissuade anyone from reading the New Testament and from placing their trust in Yeshua as Messiah. We can trust the Septuagint’s accuracy in passages quoted by the apostles, even when we cannot verify some of the quotations through pre-Christian manuscript evidence.

In conclusion, rather than assume that quotations from the Septuagint in the New Testament are Christian alterations, we should now see that the New Testament was composed during an era where Jewish people knew Greek, spoke Greek, and read the Bible in the form of the Greek Septuagint. In this first-century atmosphere, the most natural thing for writers of the New Testament to do was quote from the Greek Septuagint. The Septuagint, rather than being a liability for the New Testament, is further proof of the New Testament’s authentic Jewishness. The Jewish apostles who wrote the New Testament were not editing ancient quotations, but rather using the common tongue, in the common translation, to show that Jesus was the promised king of Israel.

Bibliography

Aitken, James K., ed. The T&T Clark Companion to the Septuagint. London; New Delhi; New York; Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Baumgarten, Albert I., and S. David Sperling. “Scroll of Esther.” Edited by Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA in association with the Keter Pub. House, 2007.

Brannan, Rick, ed. Septuagint Manuscript Explorer. Bellingham, WA: Faithlife, 2015.

Brannan, Rick, Ken M. Penner, Israel Loken, Michael Aubrey, and Isaiah Hoogendyk, eds. The Lexham English Septuagint. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012.

Burkitt, F.C., and Louis Ginsberg. “Aquila.” Edited by Isidore Singer. The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1901–1906.

Charlesworth, James Hamilton, ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1983–1985.

Clarke, Andrew D. “Alexandrian Library.” Edited by Craig A Evans and Stanley E Porter. Dictionary of New Testament Background. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000.

Daniel, Suzanne. “Bible: Translations.” Edited by Geoffrey Wigoder and Fern Seckbach. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Jerusalem, Israel: Keter Publishing House Ltd., 1997.

Di Lella, Alexander A. “Wisdom of Ben-Sira.” Edited by David Noel Freedman. The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992.

Dines, Jennifer M., and Michael A. Knibb. The Septuagint. London; New York: T&T Clark, 2004.

Fernández Marcos, Natalio. The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

Fescher, Paul V.M. “Privileged Translations of Scripture.” Edited by Jacob Neusner, Alan J. Avery-Peck, and William Scott Green. The Encyclopaedia of Judaism. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2000.

Field, Frederick and Origen. Origenis Hexaplorum Quae Supersunt Sive, Veterum Interpretum Graecorum in Totum Vetus Testamentum Fragmenta. 2 vols. Oxford, UK: E typographeo Clarendoniano, 1875. https://archive.org/details/origenhexapla01unknuoft.

Gottheil, Richard. “Bible Translations.” Edited by Isidore Singer. The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1901–1906.

Greenspoon, Leonard J. “Bible: Translations.” Edited by Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA in association with the Keter Pub. House, 2007.

Hengel, Martin, Roland Deines, and Mark E. Biddle. The Septuagint as Christian Scripture: Its Prehistory and the Problem of Its Canon. Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 2002.

Irenaeus of Lyons. Against the Heresies, Book 3. Edited by M. C. Steenberg. Vol. 64. Mahwah, NJ: The Newman Press, 2012.

Jobes, Karen H., and Moisés Silva. Invitation to the Septuagint. Second Edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2015.

K-J, Abram. “How to Read and Understand the Göttingen Septuagint: A Short Primer, Part 1.” Words on the Word, November 4, 2012. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://abramkj.com/2012/11/04/how-to-read-and-understand-the-gottingen-septuagint-a-short-primer-part-1/.

Law, Timothy Michael. When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Lohse, Eduard. “Ῥαββί, Ῥαββουνί.” Edited by Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, and Geoffrey William Bromiley. Translated by Geoffrey William Bromiley. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964.

Maimonides, Moses. פרקי אבות: Including Shemoneh Perakim, the Rambam’s Classic Work of Ethics and Maimonides’ Introduction to Perek Chelek Which Contains His 13 Principles of Faith. Translated by Eliyahu Touger. Brooklyn, NY: Moznaim Publishing Corporation, 1994.

Metzger, Bruce M., and Bart D. Ehrman. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 4th edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Müller, Mogens. The First Bible of the Church: A Plea for the Septuagint. Vol. 206. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996.

Neusner, Jacob. The Babylonian Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2011.

Norman, Asher. Twenty-Six Reasons Why Jews Don’t Believe in Jesus. Los Angeles, CA: Black White & Read, 2008.

Pick, Bernhard. “Septuagint, Talmudic Notices Concerning The.” Edited by John McClintock and James Strong. Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1891.

Rudd, Steve. “10 Archeological Proofs the Septuagint Tanakh Was Translated by Jews Before 150 BC.” The Interactive Bible. Last modified 2017. Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.bible.ca/manuscripts/Septuagint-LXX-Greek-Bible-entire-Tanakh-39-books-translated-complete-by-150BC.htm.

———. “Greek Scroll Twelve Minor Prophets Nahal Hever 50 BC: Septuagint Translation of 8HevXIIgr.” The Interactive Bible. Last modified November 2017. Accessed November 20, 2022. https://www.bible.ca/manuscripts/bible-manuscripts-Septuagint-twelve-Greek-Minor-prophets-scroll-Nahal-Hever-Bar-Kochba-Cave-of-Horrors-letters-Dodekapropheton-Greek-8HevXIIgr-50BC.htm.

Ryle, Herbert Edward. Philo and Holy Scripture: Or, The Quotations of Philo from the Books of the Old Testament. London; New York: Macmillan and Co., 1895.

Schiffman, Lawrence H. “Early Judaism and Rabbinic Judaism.” Edited by John J. Collins and Daniel C. Harlow. The Eerdmans Dictionary of Early Judaism. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2010.

Segal, Moshe Zevi. “Wisdom of Ben Sira.” Edited by Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA in association with the Keter Pub. House, 2007.

Shapiro, Marc B. The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles Reappraised. Portland, OR: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004.

Singer, Tovia. “A Christian Defends Matthew by Insisting That the Author of the First Gospel Relied on the Septuagint When He Quoted Isaiah to Support the Virgin Birth.” Outreach Judaism, n.d. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://outreachjudaism.org/septuagint-virgin-birth/.

———. “A Closer Look at the ‘Crucifixion Psalm.’” Outreach Judaism, n.d. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://outreachjudaism.org/crucifixion-psalm/.

———. “Is the Septuagint A Theological Crime Scene?” Outreach Judaism, n.d. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://outreachjudaism.org/is-the-septuagint-a-theological-crime-scene/.

———. Let’s Get Biblical. New Expanded Edition. 2 vols. Forest Hills, NY: Outreach Judaism, 2014.

Skolnik, Fred, and Michael Berenbaum, eds. “Septuagint.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA in association with the Keter Pub. House, 2007.

Soderlund, S.K. “Septuagint.” In The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, edited by Geoffrey William Bromiley, 4:4:400-09. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988.